The 9 June 2020 marks 150 years since the death of Charles Dickens, the most famous writer of his time, whose celebrity status was probably comparable to that of a film star today.

We know that the 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858) attended a private theatrical organised by Dickens in 1845, and that in the same year, Dickens paid a brief visit to Chatsworth – or more accurately to the house of Head Gardener Joseph Paxton, who was financially backing a newspaper which Dickens was to edit.

However, the first archival evidence of any direct contact between the writer and the Duke comes in the form of a letter dated 4 March 1851: Dickens wrote to ask whether the Duke would consider hosting an amateur performance at his London home, Devonshire House, in the presence of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

The play to be performed was a comedy called Not so Bad as we Seem by Edward Bulwer Lytton, a writer and friend of Dickens. The two men were planning to establish an organisation called the Guild of Literature and Art which would provide financial assistance to authors, helping to professionalise writing as a career; the performance was to be a fund-raiser. Dickens enclosed a copy of their prospectus, telling the Duke ‘there is no other gentleman in this land whom I would so trouble. Simply because there is no other on whose generous attachment to Letters and Art, I so implicitly rely’.

Dickens was an expert at flattery, and in this case it worked: the Duke was delighted to provide all the help he could, and immediately wrote to court official Sir Charles Phipps to enquire about how best to approach the Queen. The royal couple accepted the invitation, so preparations began.

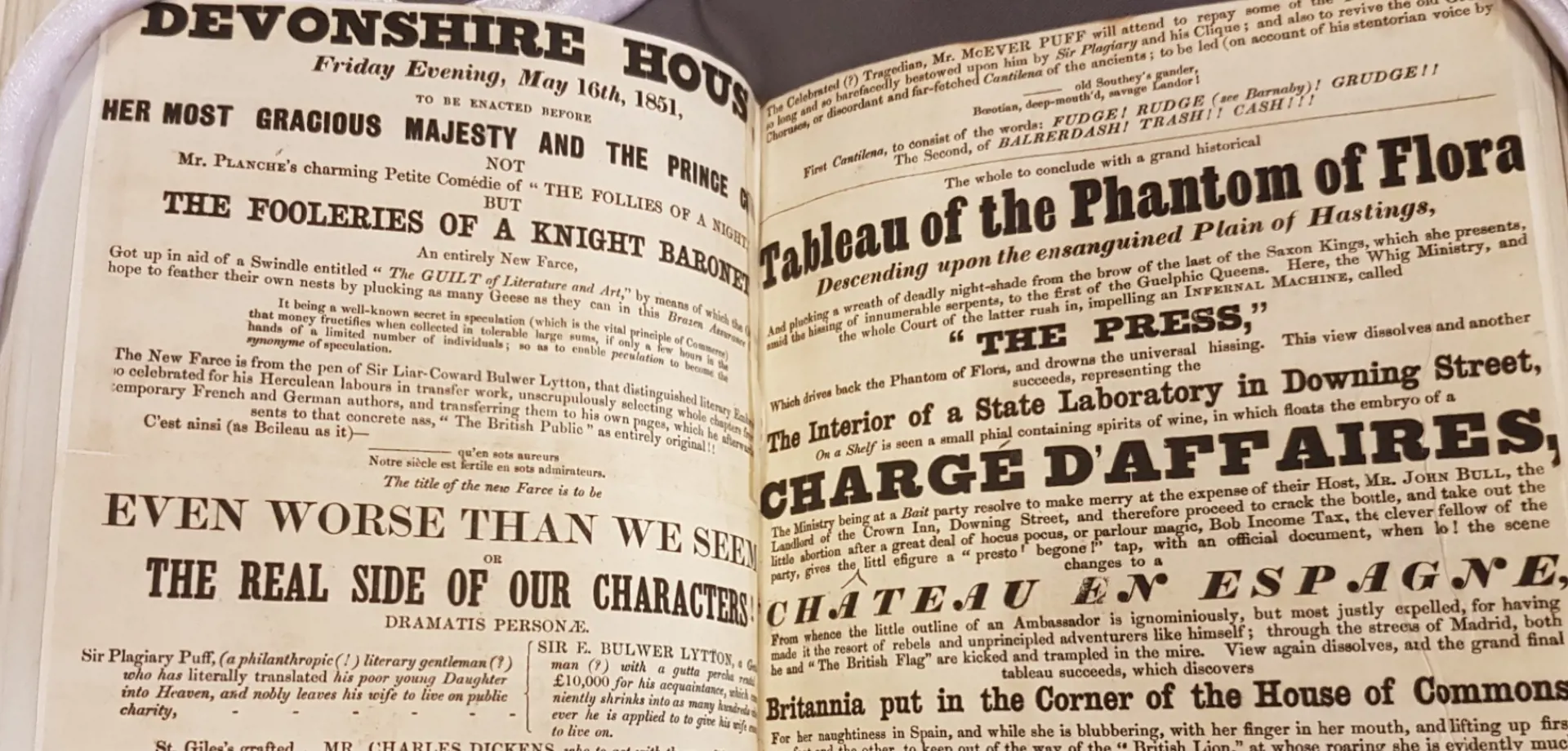

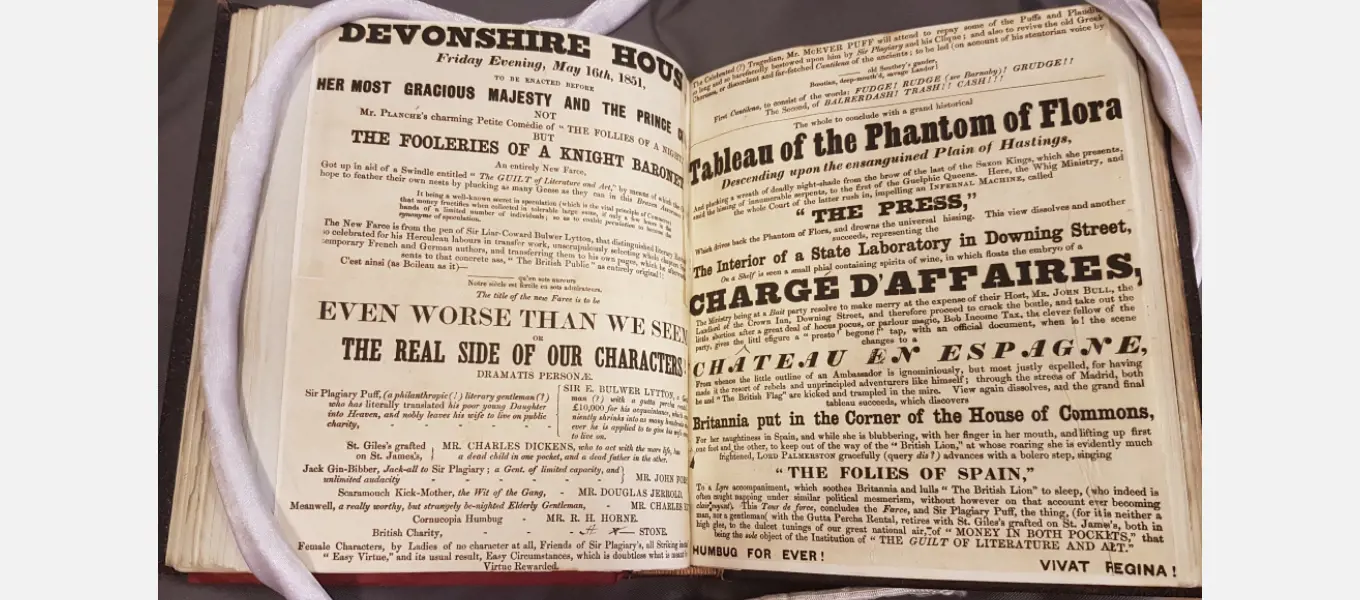

Opening night was scheduled for 16 May, with advertisements and playbills being circulated to publicise the performance. What none of those involved had anticipated was the intervention of Bulwer Lytton’s estranged wife, Rosina. The couple had separated acrimoniously in 1836, following tensions over money and Bulwer Lytton’s infidelities; Rosina was denied access to the couple’s children and was only able to visit her daughter when the latter was dying of typhoid fever aged 19 in 1848.

Understandably bitter, Rosina spent the rest of her life trying to publicly shame and humiliate her husband – partly through her own novels which often focused on the plight of women in similar situations to her own.

Having presumably seen one of the playbills for Not so Bad as We Seem, she decided the royal performance would be a perfect opportunity to embarrass her husband. In the run-up to opening night, she wrote to some of the key figures involved, including the Duke, stating her intention to attend the performance dressed as a beggar girl and pelt her husband with rotten eggs.

Dickens took the matter in hand and decided to call on the assistance of Inspector Charles F. Field of Scotland Yard, who was an acquaintance of his and is generally believed to have been the model for Inspector Bucket in Bleak House.

Dickens wrote to the Duke on 9 May: ‘I have spoken to Inspector Field of the Detective Police…and have requested him to attend Mr Wills [Dickens’s friend and sub-editor] on both nights in plain clothes. He is discretion itself, and accustomed to the most delicate missions. Upon the least hint from Mr Wills, he would show our fair correspondent the wrong way to the Theatre, and not say a word until he had her out of hearing – when he would be most polite and considerate’.

Rosina Bulwer Lytton went to the length of having a spoof playbill printed which parodied the one that had been circulated to advertise her husband’s play: retitling it Even Worse than We Seem, she used the bill to attack her husband and most of the cast. The playwright was given as Sir Liar-Coward Bulwer Lytton, and the character he played in the drama itself as ‘Sir Plagiary Puff, a philanthropic (!) literary gentleman (?) who has literally translated his poor young Daughter into Heaven, and nobly leaves his wife to live on public charity’.

Professor Michael J. Flynn of the University of North Dakota has researched this episode and only uncovered two surviving copies of the parody playbill: one at Chatsworth, and one at Knebworth, the family seat of the Bulwer Lyttons. In light of this, he suggests that Rosina may have appeared on the night to hand out her playbills and try to gain entry to the performance, but that Field and Wills intervened and took possession of the bills before she had a chance to distribute them.

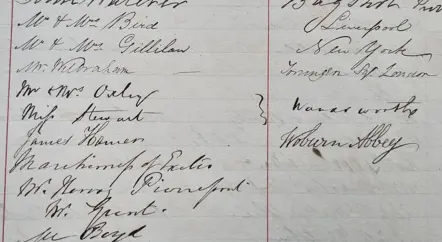

The 6th Duke kept scrapbooks and albums recording many of his activities, and there is an album dedicated to the performance, containing the letters he received from Dickens, the Guild’s prospectus, invitations, lists of invited guests and cuttings of reviews. He also carefully pasted in a copy of the parody playbill. He (tactfully) returned Rosina’s letter to her so that never made its way into his archive.

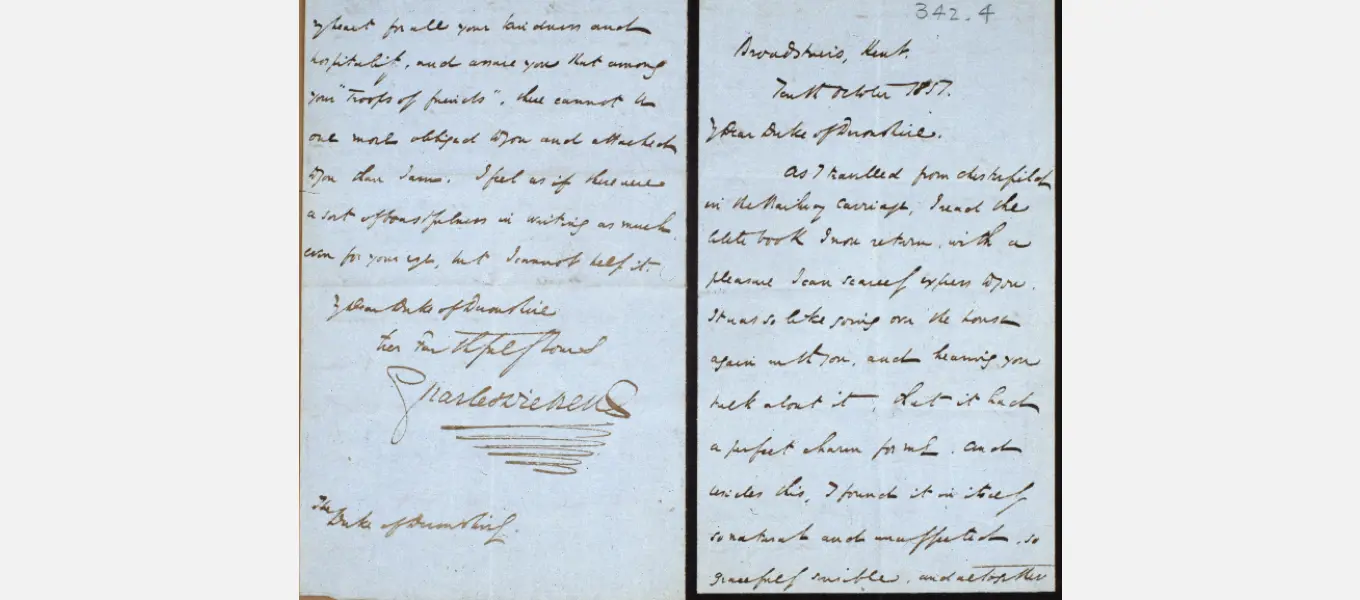

The performance marked the start of an enduring friendship between Dickens and the Duke. In October of that year, Dickens stayed at Chatsworth as a guest, and was lent a copy of the Duke’s Handbook of Chatsworth and Hardwick, privately printed in 1844. The Duke intended the book for family and close friends, and it provides an engaging, entertaining and very personal room-by-room tour of each house. Dickens immediately recognised the Duke’s literary ability. He read the Handbook on the train on the way back to London, and wrote to the Duke:

‘As I travelled from Chesterfield in the railway carriage I read the little book I now return with a pleasure I can scarcely express to you. It was so like going over the house again with you, and hearing you talk about it, that it had a perfect charm for me. And besides this, I found it in myself so natural and unaffected, so gracefully sensible, and altogether so winning and so good, that I read it through, from the first page to the last, without once laying it aside.

I could mention some things in it which would require a very nice art to do as well in fiction. The little suggestive indications of some of the old servants and old rooms – and childish associations – are perfect little pieces of truth’.

The Duke would have been extremely gratified at receiving such praise from the greatest writer of his day. Although Dickens never visited Chatsworth again, the two men met occasionally in London and continued their correspondence until the end of 1856, just over a year before the Duke’s death.

For anyone interested in reading more about the Devonshire House performance and associated events, see Michael J. Flynn’s article ‘Dickens, Rosina Bulwer Lytton, and the “Guilt” of Literature and Art’, in the Dickens Quarterly, vol. 29 (March 2012), pp. 68-80.