Watch

Commissioned in 1846 by the 6th Duke of Devonshire, the Veiled Vestal was Raffaelle Monti’s first veiled figure—an extraordinary work that helped launch his career. Learn how ancient Roman symbolism and Victorian ideals combine in this marble masterpiece.

We use platforms such as YouTube and Vimeo to display videos. These require the use of cookies, for which we need your consent. To watch this video, please click here to allow cookies.

Video Transcript:

There is something almost magical about this sculpture - Raffaelle Monti’s Veiled Vestal. Carved from Carrara marble, the delicate veil seems impossibly translucent, a masterful illusion created in stone. But beyond its artistry, this sculpture holds a unique place in history.

Commissioned by William, 6th Duke of Devonshire, on the 18th of October 1846, this was Monti’s first recorded veiled figure - a motif that would come to define his career.

Portrait of the 6th Duke of Devonshire

The Duke, captivated by Monti’s skill, paid £60 in advance for the work, effectively ‘introducing’ the young sculptor to the British public. Just two years later, Monti moved permanently to England, where he would achieve lasting fame, setting up his studio at 45 Great Marlborough Street, London, and working there until his death in 1881.

Portrait of Raffaelle Monti by Camille Silvy, November 2, 1860. Albumen print. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

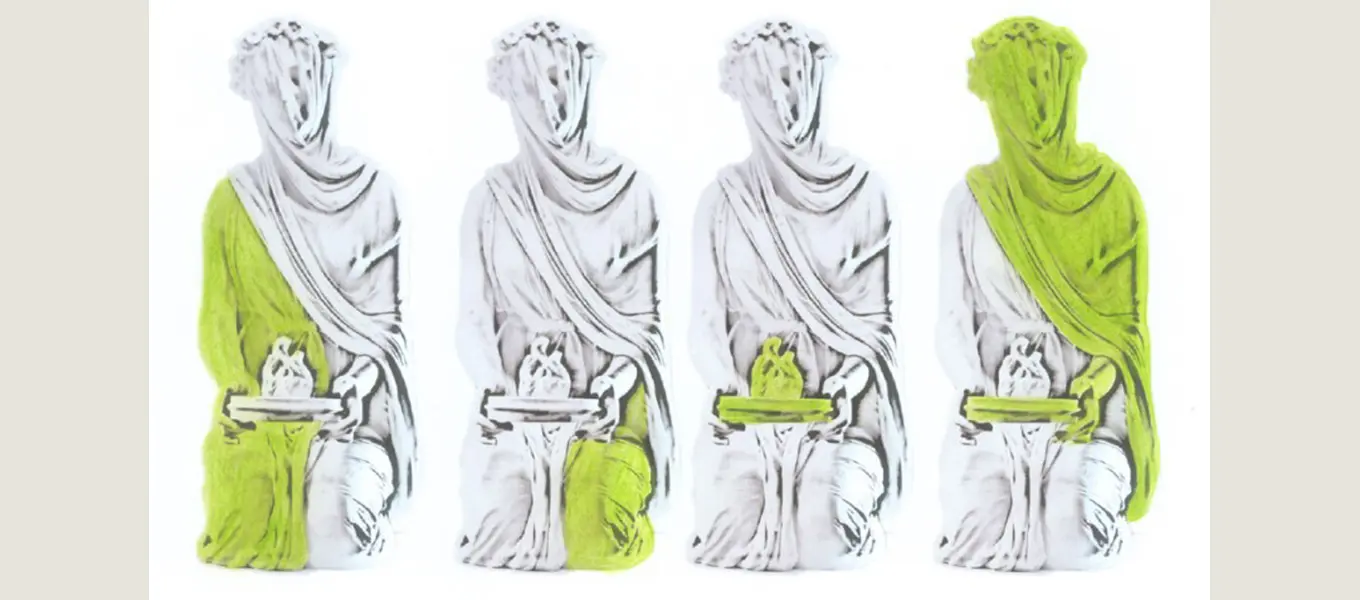

The Veiled Vestal was a technical feat. Carved in the round from three primary blocks of Carrara marble, it was assembled in a specific order - the base first, then the body, with the final section being the head and veil, carefully placed over the figure. Monti’s ability to create the illusion of gossamer-thin fabric in solid stone was astounding, and it set the standard for veiled sculpture in the 19th century.

Image showing the composite parts of the Veiled Vestal

The sculpture’s journey has been as fascinating as its creation. First recorded in an inventory at Chiswick House in 1863, it remained there as the villa was rented to various tenants - including the Duchess of Sutherland, the Prince of Wales, and the 3rd Marquess of Bute. In 1892, it moved to Compton Place before finally being brought to Chatsworth by the 11th Duke of Devonshire in 1999.

Engraving "A view of the Rt. Hon.ble the Earl of Burlington's House at Chiswick; taken from the Road", by John Donowell, c. 1760-1766

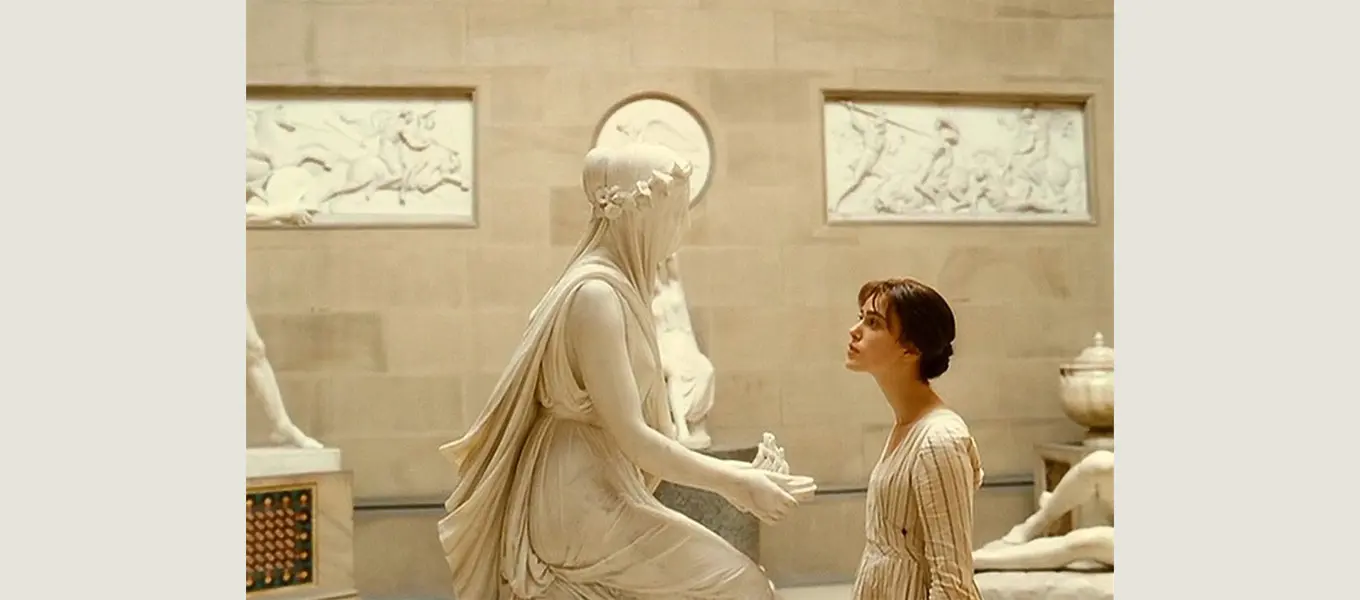

Since then, it has been displayed in multiple locations, including the Oak Room, the Grotto, and the Dome Room. The sculpture featured in the 2005 film production of Pride and Prejudice, which cemented its place as a highlight of the Devonshire Collection.

Still captured from 2005's Pride and Prejudice © Working Title Films, in association with StudioCanal

The sculpture was also lent to Tate Britain’s Sculpture Victorious exhibition in 2014 and to Sotheby’s New York in 2019 as part of Treasures From Chatsworth.

Image of the sculpture being prepared to send out on loan, by Chatsworth technicians

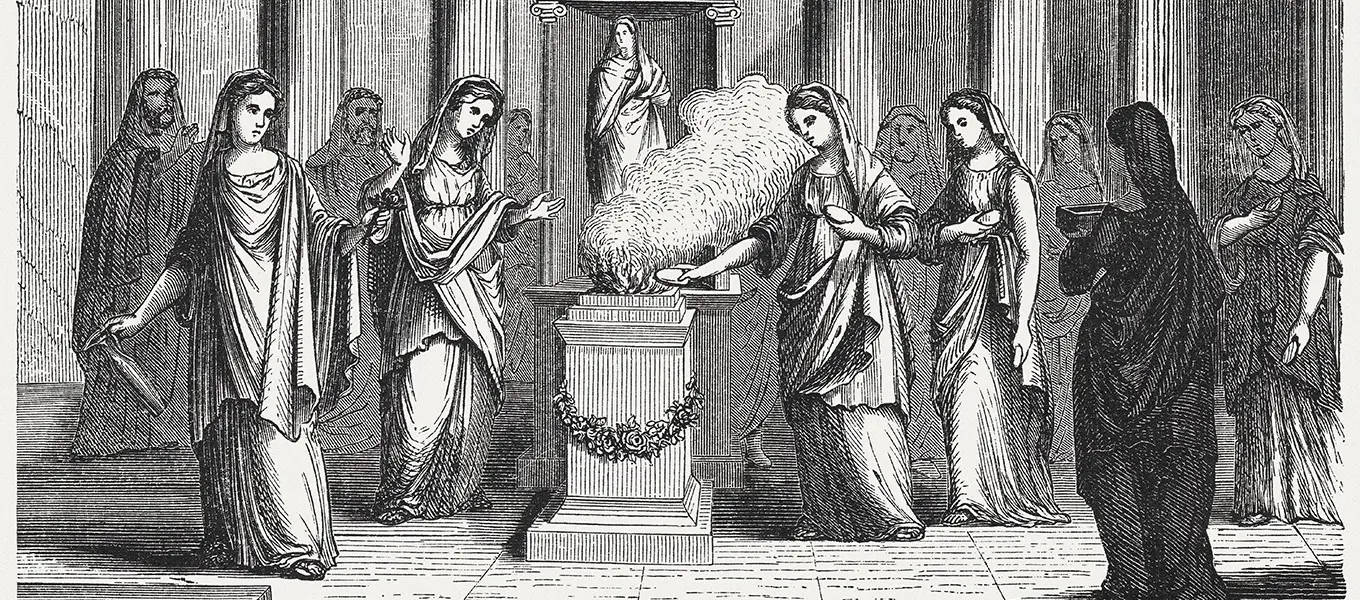

But what of the figure itself? The sculpture represents a Vestal Virgin - one of the six priestesses of Vesta, guardian of Rome’s sacred hearth flame. The Vestals’ duty was to keep the eternal fire burning, a symbol of the city’s strength and stability.

Illustration of the Vestals tending Rome’s sacred hearth flame

To maintain their purity, they took a strict vow of chastity for thirty years. Their virginity was believed to give them great power, as their energy, undistracted by marriage or motherhood, was thought to be entirely devoted to Rome’s welfare. Yet, they were not isolated figures - unlike most women in Roman society, Vestals were free from their fathers’ legal authority, could inherit property, and even attend private dinners and state events.

Louis Hector Leroux: Vestal virgins at the Roman Colosseum - accessed via Wikimedia Commons

Unlike other Roman women, who were often excluded from public life, Vestals sat in special front-row seats at public games - privileged observers of the spectacles denied to most of their peers. Revered for their chastity, the Vestals were granted freedoms and status far beyond that of ordinary Roman women.

Image of the Veiled Vestal, displayed in the Dome Room at Chatsworth

Monti’s Veiled Vestal embodies this unusual position. The veil is a symbol of purity and mystery, but also of restriction - a barrier between the Vestal and the world. When the sculpture was completed, it spoke to Victorian ideals of femininity: the 19th century was fascinated by the idea of the virtuous, untouchable woman, and Monti’s work captures both the beauty and the burden of that role.

From its creation in Milan to its place in the Devonshire Collection, Monti’s Veiled Vestal remains one of the most exquisite and enigmatic sculptures of the 19th century. A work of unmatched technical skill, rich in symbolism, and layered with meaning - both ancient and modern.