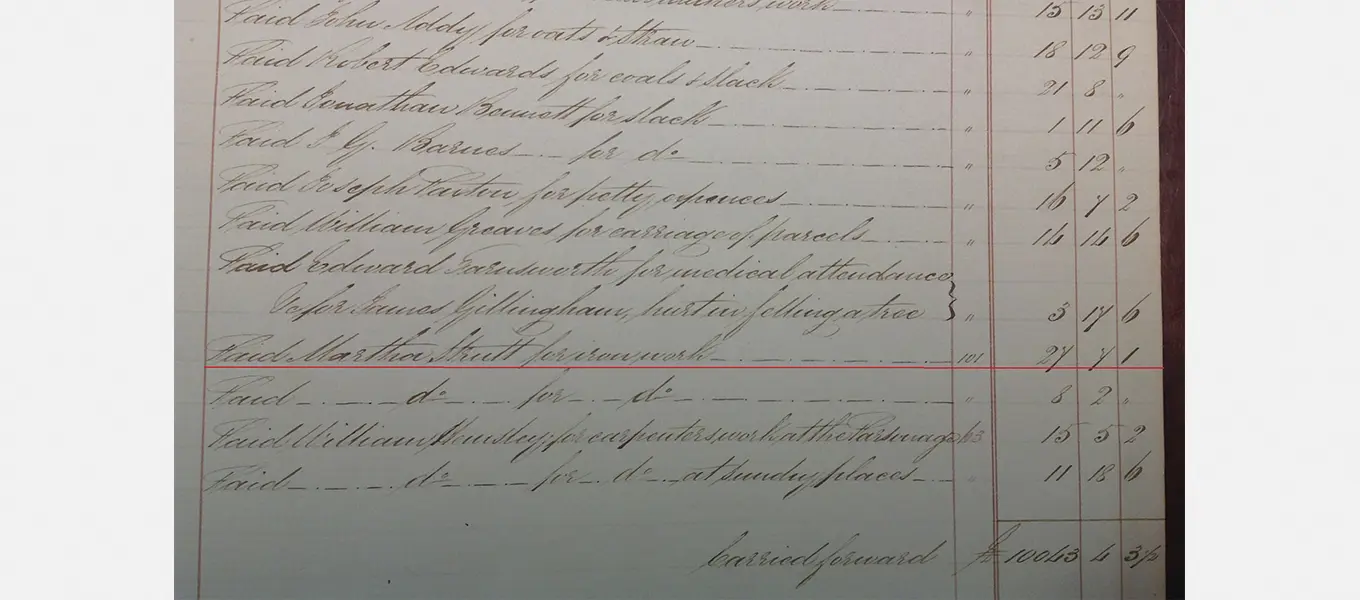

There is an unusual entry in the Chatsworth estate account books for January 1839. Underneath a payment for medical attendance for a man injured while felling a tree, it says - ‘Paid Martha Strutt for ironwork… £27.7.1’. The hot, smoky blacksmith’s forge is not a place we associate with historical women (unless, perhaps, you are a fan of 2001 film A Knight’s Tale). So, who was Martha Strutt?

Martha Strutt’s story is closely tied to the story of old Edensor, Chatsworth’s lost estate village. Over the last few weeks, archaeologists and historians around Britain have been grabbing their drones and heading outside to photograph the parch marks left on the ground by this summer’s heatwave. Parch marks are caused by solid features such as masonry in the ground, which limit the growth of plants in the shallow soil above them and cause them to dry out first in hot weather. At Chatsworth, the Edensor high street has become visible two centuries after it was demolished, including traces of a building which is marked on a 1785 map as the blacksmith’s house.

The resident blacksmith in 1785 was John Strutt, whose grandson married a local woman named Martha White. On the 17th March 1828, in St Peter’s Church at Edensor, Martha married into an estate dynasty of blacksmiths named John Strutt. She moved into the Strutt family home, two doors down from the workshop, to start her new life as a wife, and soon as a mother. After a decade of marriage, life took a dramatic turn for Martha. In the space of four years, she lost a husband, a son, a home, and the workshop that had been in her husband’s family for generations.

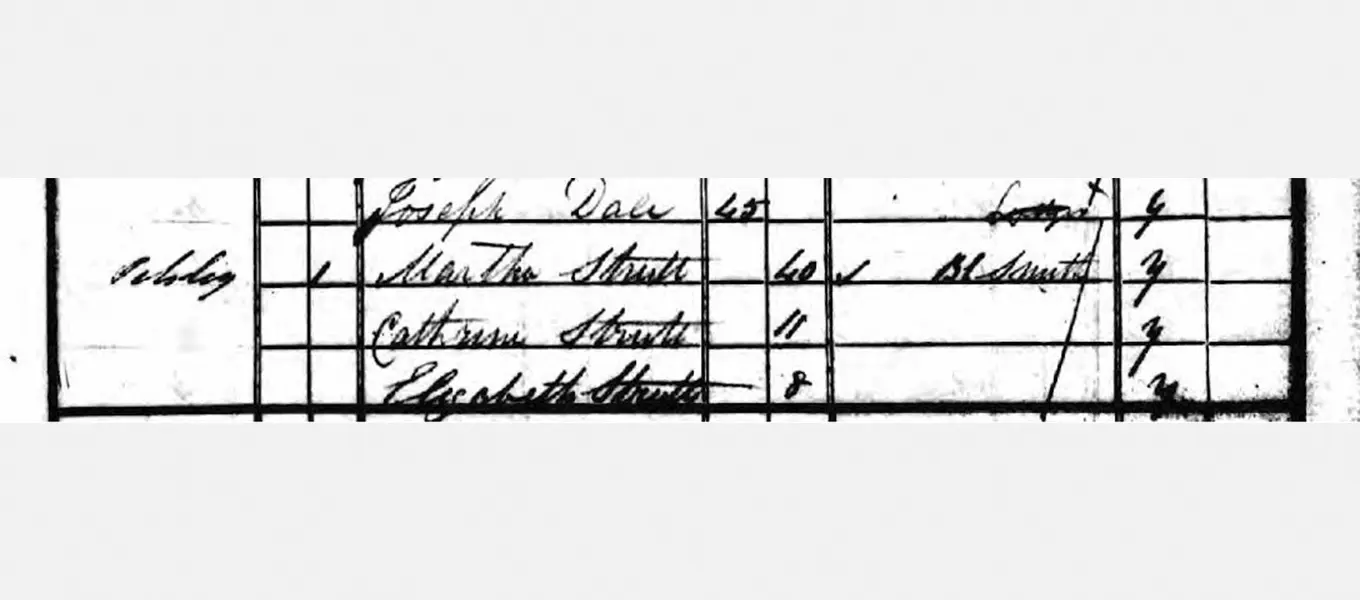

The line of blacksmiths named John Strutt ended in 1837 when Martha's husband died, shortly followed by the youngest of their five children. Two John Strutts, aged 40 and aged 8 months, appear on the same page of the parish burial records. Since the remaining children were still too young, now-widowed Martha took over the family business. Female blacksmiths were not as rare as we might expect, and by the mid-nineteenth century women and children dominated the nail-making workforce. Martha had apprentices, so did not do all of the manual labour herself, but the accounts show that she was renting and managing the blacksmith's shop in her own name. However, no sooner had she taken over the house and shop than plans were being made to demolish them. Demolitions had begun along Edensor high street in 1817, but they stepped up in 1837 as the Duke’s plans began in earnest. A smart road replaced the residential street, taking visitors to Chatsworth past the grand new village rather than through it.

The smithy was demolished later than the other buildings, perhaps because Martha’s forge was in use while building works were underway in the village. In 1841 the rental accounts record that Martha Strutt was ‘removed from Edensor’ and given a ‘new House & Blacksmith’s Shop’ in Pilsley, a mile away. The new Edensor was designed to be a ‘model’ village, showcasing the highest standards of morality and conduct that Victorian workers could aspire to. A description of Edensor in 1872 states, ‘there is neither a village ale-house, blacksmith’s forge, wheelwright’s shop, or any other gossiping place ; and unpleasant sights and discordant sounds are alike unknown’. Martha’s noisy, smoky blacksmith’s shop did not fit into the idyllic new village.

Martha’s family was one of many who never moved back to Edensor after its facelift. The population of the village had decreased by around 40% by the time of the 1841 census and continued to decline steadily thereafter. This was partly because the Duke forbade more than one family from living in each house as had been common before. Cholera was a constant concern in the 1840s, and people were becoming aware of the connection between deadly diseases and crowded housing.

It is impossible to guess how Martha and her family felt about relocating to Pilsley. It was not far from Edensor, so they were probably already familiar with their new environment. The house to which they were relocated, on the edge of the village green, is among the grandest and most picturesque in Pilsley, and here Martha was able to continue the business of her husband’s family in a new workshop built at the back (now a double garage). Her son Levi Strutt trained here to become a blacksmith like his father. Her daughter Anne found a husband, William Swindell, in Pilsley. While the demolition of Edensor coincided with a time of great personal loss for Martha Strutt, then, it also signified a fresh start for Chatsworth's blacksmith and her family.