Volunteer Leah Lucas is working on a project to catalogue some of the printed pamphlets which form part of Chatsworth’s Library, and reports on a recent find.

“He Salutes and kisses the prince as close as any Christian woman would, and the prince salutes and kisses him back again as favorily, as he would (I will not say any Alderman’s wife, but) any Court-Lady!” – Quote from the Pamphlet Observations Upon Prince Rupert’s White Dog Called BOY.

Extremely famous, Prince Rupert was handsome, young, brave and dashing, a model Cavalier of the 17th century. The nephew of Charles I, Rupert entered the court of England in his teenage years, started his military career at 13 and was imprisoned in Linz by the age of 19. It was here that he was gifted an extremely rare white hunting poodle by the Earl of Arundel who, concerned for his welfare, believed the dog would keep him company and possibly sane. The prince named the dog Boy and the two became inseparable.

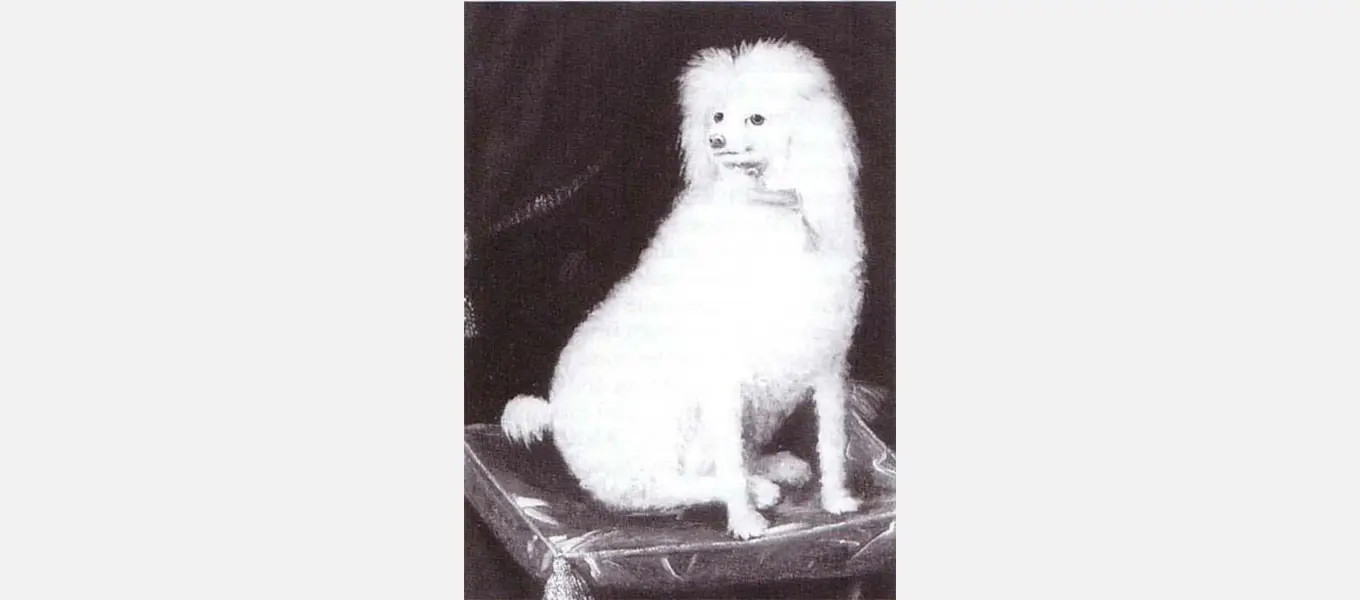

Boy said to belong to Prince Rupert of the Rhine (1619-1682).

Despite numerous attempts to seize Linz and free Rupert by the Franco-Swedish Army, his release was ultimately negotiated through Leopold and Empress Maria Anna - in exchange for a promise, to never again take arms up against the emperor. To which the prince happily acceded, kissed the emperor’s hand and left Germany for England. Upon his return Rupert was appointed General of Horse, a coveted position in which he greatly excelled. Establishing himself quickly as a great leader, and undefeated – he was a hero amongst many young Royalists and an abomination to Parliamentarians, who quickly started up a pamphlet war against the prince, taking almost any opportunity to turn propaganda into publication. Boy became notorious amongst the Parliamentarians, often featuring heavily in their libellous pamphlets too.

Copious accounts of Boy and his ‘abilities’ were written, many claiming he was the devil. Most commonly he was believed to be a witch’s familiar, facilitating Rupert in his battles, using witchcraft to secure the Royalist position. There were accounts of shapeshifting, magic, witches, spying, even the tale that upon hearing the name of John Pym, leader of the Parliamentarian forces, Boy would cock his leg and urinate.

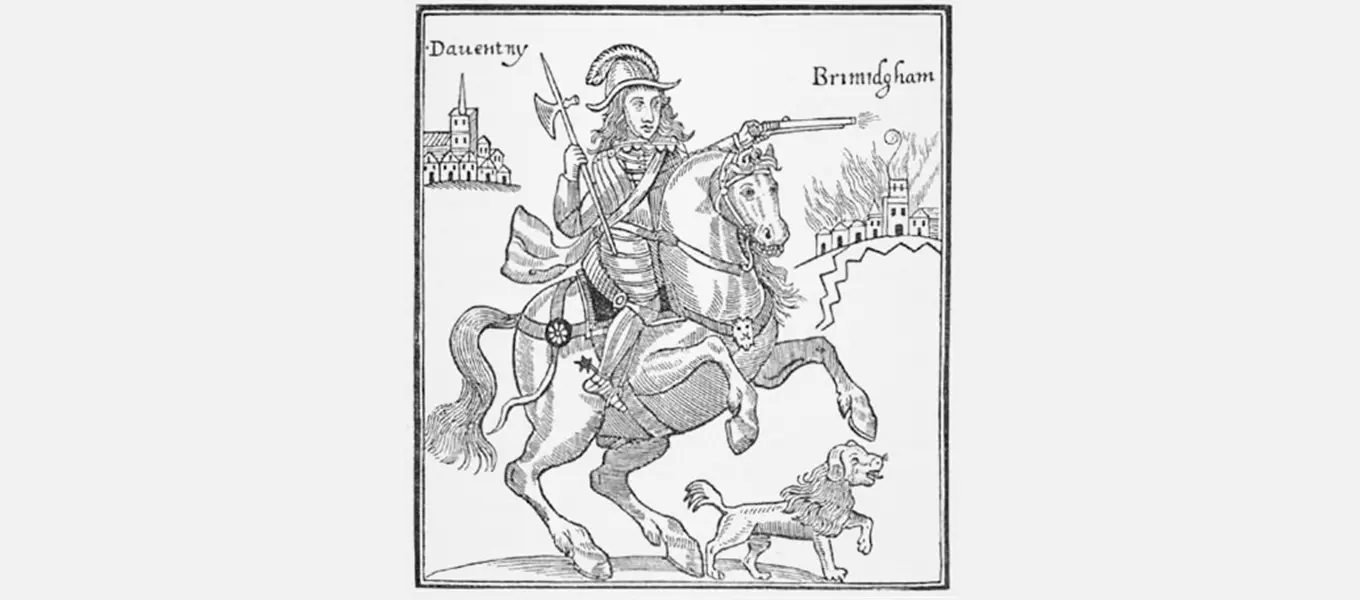

One of the best-known Parliamentarian pamphlets on Boy is ‘A True Relation of Prince Rupert’s Barbarous Cruelty against the Twone of Brumingham.’ which displayed a frontispiece of a burning town, Rupert on horseback and a tiny lion standing at the horse’s feet. That lion was Boy (seen in the image below).

Frontispiece of the Parliamentarian pamphlet ‘A true relation of Prince Rupert's barbarous cruelty against the towne of Brumingham’, showing Prince Rupert attacking ‘Brumingham’ during the Battle of Birmingham in 1643.

Another famous ‘Cavaliers v Roundheads pamphlet’ was humorously styled: ‘A Dialogue, or, Rather a Parley Betweene Prince Ruperts dogge Whose Name is Puddle (Boy), and Tobies dog Whose Name is Pepper, &c.’’ which shows a cartoon of the two dogs exchanging insults (seen in the image below).

Page from the royalist propaganda pamphlet A Dialogue, or Rather a Parley Between Prince Ruperts Dogge Whose Name is Puddle, and Tobies Dog Whose Name is Pepper issued in London c. 1643.

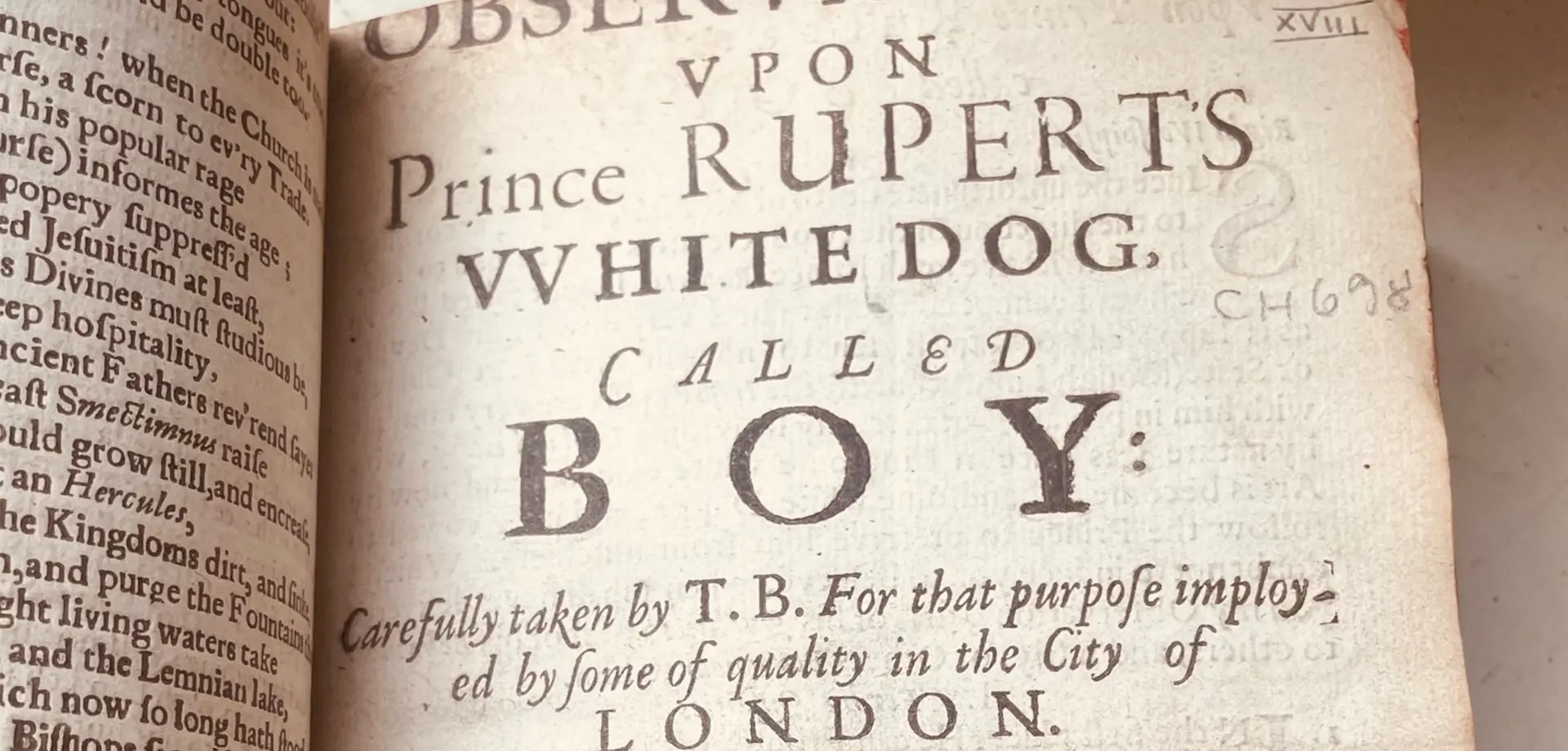

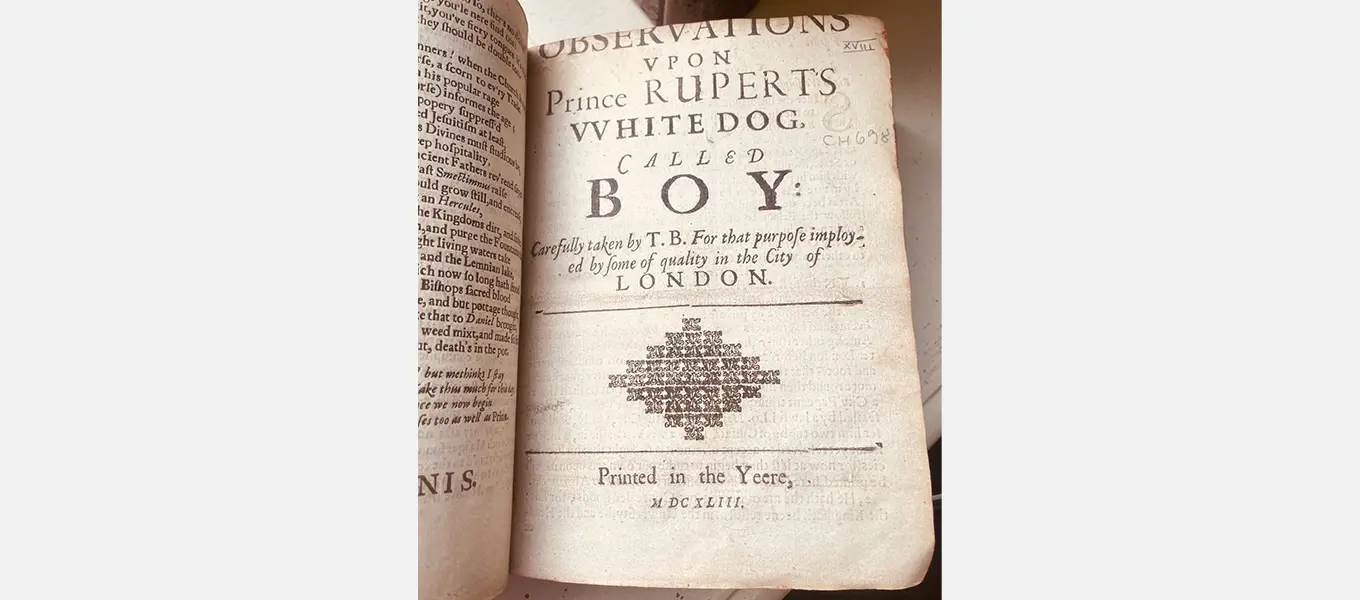

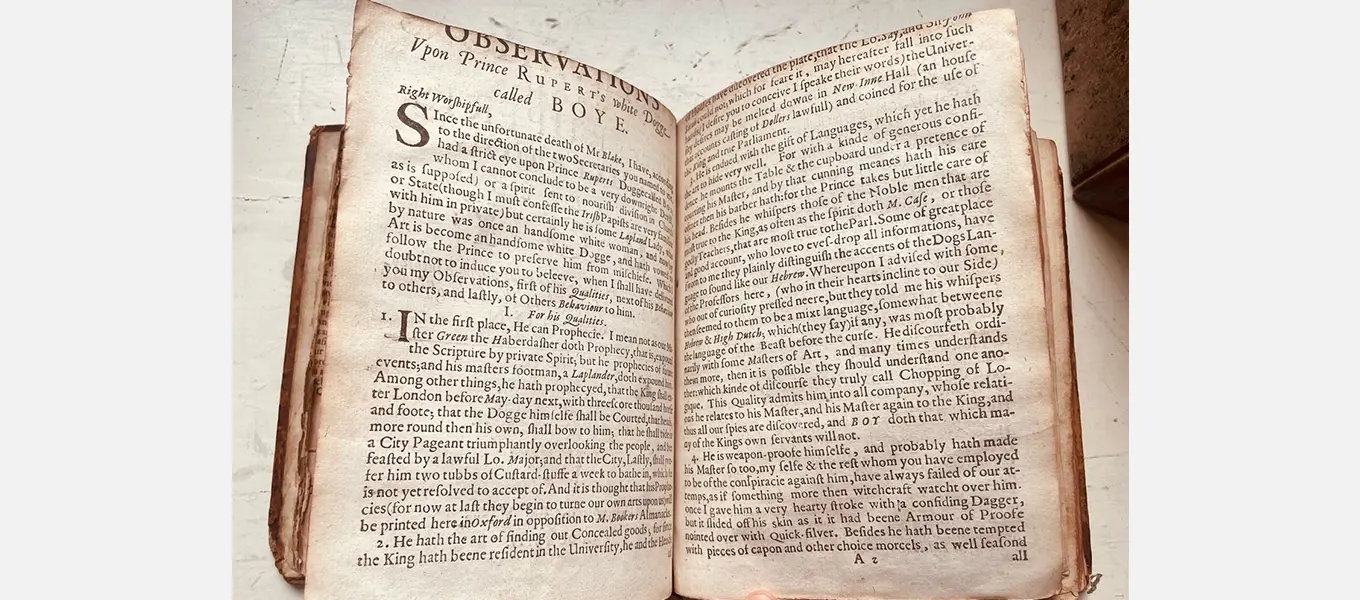

This Parliamentarian superstition towards Boy, and their obsessive demonising of the little white poodle, caught the attention of Royalist satirists, who mocked and ridiculed such attitudes in their own parodies and pamphlets. One satirist’s publication claimed that Boy was a shapeshifting ‘white woman’, some ‘Lapland Lady’, ‘who by nature was once a handsome white woman, who by some art is become an handsome white Dogge’. It is here in the Chatsworth archives that we have come across such a story. Bound in a leather volume, amongst 52 other pamphlets, is a copy of the ‘Observations upon Prince Rupert’s White Dog Called Boy’, a satirist piece published in 1643.

“Observations upon Price Rupert’s White Dog named Boy” 1643, from the Devonshire Collection Library.

The piece makes claims that Boy ‘can prophecie’, is ‘endued with the gift of many languages’ and ‘is ‘weapon-proof himselfe!’ –with the author claiming he once ‘gave him (Boy) a hearty stroke with a confinding Dagger, and it slided right off his skin as if it has beene Armour of Proofe noited over with Quick Silver!’ Best of all the claims is that Boy could also go invisible and in doing so had the power to make others invisible too.

The most endearing assertion of all accounts from both sides (Parliamentary and Royalist) is the very real relationship outlined between a young prince and his dog, a witch’s familiar or in Phillip Pullman’s fictional world of the Northern Lights, his Daemon. Boy accompanied Rupert into many battles, he slept in his bed, they kissed, cuddled and dined by each other’s side like kings.

It was written that Boy loved no one more than the prince, though next to him he loved the king and all the kings’ children: ‘more than he cares for any other’. It was recorded that when the sixth Alderman delivered the city petition to the King, ‘Boy lay just before Alderman Garret, eyes fixed on the King and the Prince Rupert, with one foot placed upon the King’s foot and the other on Prince Charles’ (Charles II).

Boy died during the Battle of Marsden Moor in 1644. Accounts recall that he had initially been left safely tied up in the Royalist camp. Rupert’s horse was shot whilst he was riding, prompting him to take cover in a field. After some time, Boy broke free and in search of the prince. Some pamphlets claimed the ‘White Dog named Boy’ had been bullet proof, but sadly he never reached the field. One of the last pamphlets written about the magic dog named Boy read:

‘To tell you all the pranks this Dogge hath wrought,

That lov’d his Master, and him Bullets brought,

Would but make laughter, in these times of woe…’