Watch...

Gem collecting began in ancient times, but experienced a renewed popularity during the Renaissance and in the 18th century, when wealthy and fashionable society undertook extensive tours of Europe, collecting art, sculpture, and antiquities to display in their homes.

The 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 6th Dukes of Devonshire were all passionate collectors and the Devonshire collection preserves many examples of carved gems dating back to the 1st century BCE.

Chatsworth's curator of decorative arts, Sash Giles, explores the provenance of some of the gems in the collection, and how they were often given a practical use.

You can also read a transcript of this video, with illustrations, below.

View the carved gem collection

Monday 24 April 2023 | 9.30am - 12.30pm

Join Sash Giles on a private guided tour of the house, including the opportunity to view some of the rare carved gems in the Devonshire collection up close in our curatorial study room. Event tickets are priced at £55 and include house and garden entry.

Read...

William, Second Duke of Devonshire (1672-1729) sat for this portrait painted by Charles Jervas (1675-1739). The painting still hangs at Chatsworth along with the gems and cabinet also in the portrait.

The Duke chose to be portrayed seated in a relatively small scale, his eyes are level with ours as he invites us to join him in spending time looking at and learning about his collection.

Perhaps we will discuss the literature around the subject, or look at prints and drawings depicting the same subjects. We may also talk of other collections and collectors, and together share our knowledge and interest.

This portrait places us, the viewer, on the same level as the Duke, both physically but also perhaps, socially. We are being admitted to an intimate and private space away from the public arena.

The survival of the painting, the cabinet and the gems together at Chatsworth gives us an opportunity to experience these objects today in a similar way to the 2nd Duke.

The cabinet made by the French cabinetmaker Andre Charles Boulle contains a series of drawers in which the Duke would have arranged his gems. Each drawer is lined with red velvet and fitted as a tray with compartments so that each drawer can be taken out, placed on a desk or table and each gem taken out to be looked at. Collectors of gems, medals, and coins commissioned cabinets like this one to securely house their collections, but also to emphasise how precious the contents were.

Carved gems were prized in ancient cultures and Pliny the elder (AD 23/24 – 79), the Roman writer and naturalist, records that it was General Pompey who popularised gem collecting in Rome. He dedicated the collection of King Mithradates (164-63 BC) in the Temple of Jupiter Capitoline as Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.) would also do at the Temple of Venus Genetrix. Carved gems and cameos were seen as appropriate gifts in tribute and thanks to the gods.

Carnelian Intaglio of Serapis, the Greco-Roman Sun god. 100 BCE-100 ACE.

Sardonyx cameo depicting Diana, Mars and Cupid. C.1525.

Carved gems made from precious and semi-precious stones are actually small sculptures, known as a glyptic art from the Greek gluptos ‘to carve’.

Gems fall into two categories; intaglio where the design is etched and carved into the stone itself, or cameo where layers of different colours are pared away to create an image in relief.

Gem collecting, which began in ancient times, again became popular during the renaissance, a time in Europe when interest in Roman and Greek culture was revived and the statues, architecture, literature and history of those past cultures was studied and appreciated. The renaissance carver Valerio Belli (1468–1546) refined ancient techniques creating what were at the time modern masterpieces in an ancient tradition.

Gem collecting once again became fashionable in the eighteenth century, when Europeans travelled across the continent visiting sites of interest, collecting ancient sculpture and art on their way and bringing them back for appreciation and display in their homes. This phase of collecting laid the foundations for the creation of the earliest public museums.

The stones are usually mounted in a precious metal, most usually gold and worn as rings or pendants, later intaglio stones were set into fobs and worn with watches or used as desk seals much as they were originally.

The development of formal archaeology and excavations in Greece, Rome and the Middle East saw ancient gems and copies adopted as fashionable accessories, mounted in to every day jewellery.

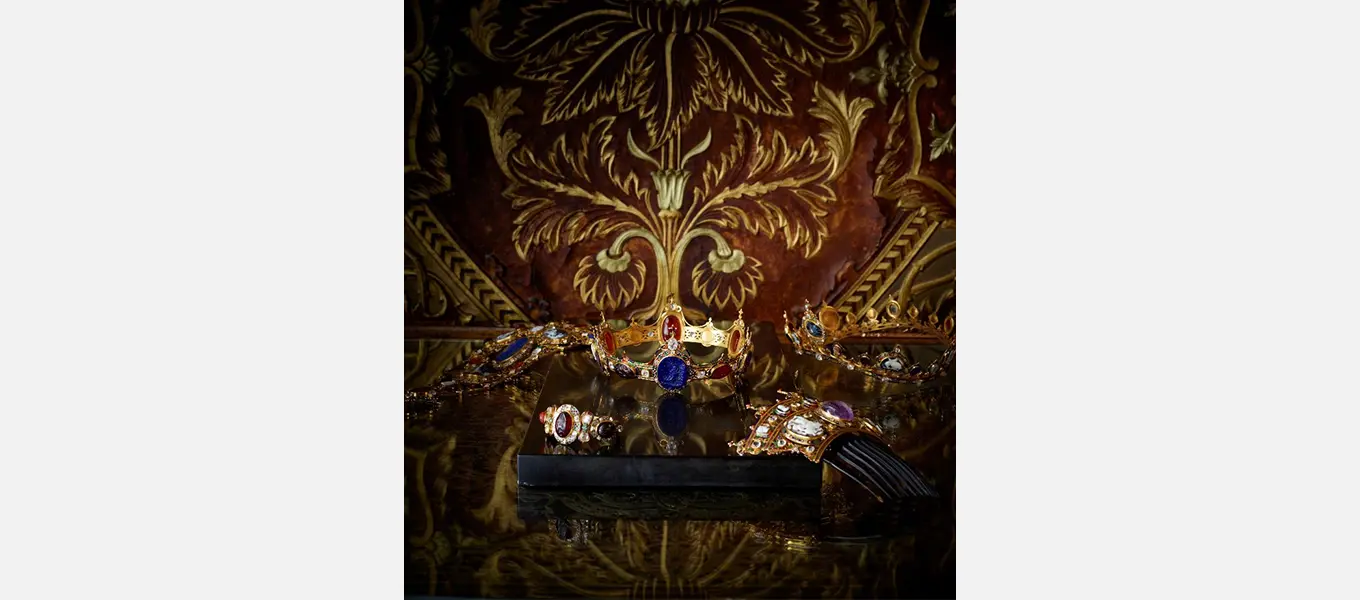

Necklace from the Devonshire Parure. 1856.

The first and most prolific collector of the carved gems in the Devonshire collection was William, 2nd Duke of Devonshire (1673-1729), his interest was shared by both his son, grandson and great-great grandson, the 3rd, 4th and 6th Dukes.

The 2nd Duke collected gems, medals, coins, furniture, drawings, and paintings and it was his collection, augmented by the Burlington inheritance, which forms the bedrock of the present Devonshire collection.

The 2nd Duke belonged to a generation of English collectors who benefited from earlier collectors, including Thomas Howard, the Earl of Arundel (1585-1646), and Charles I in England, and Lorenzo de Medici and Pope Paul II on the continent.

Collecting in England was however largely interrupted by the civil war and it was the Duke’s generation that enjoyed relative peace and opportunities for travel to Europe. The collections formed by the Earl of Arundel (1585-1646) and Charles Spencer, 3rd Duke of Marlborough (1706-1758), have been dispersed; sold by their original owners, and parts of them are now held in collections across the world.

The Grand Tour afforded access to both ancient and modern gems which could be bought, collected, and enjoyed in their homes. Appreciation of carved gems demonstrated a worldly authority, a knowledge of myths, and ancient rulers and were a mark of an educated mind.

A series of letters between Baron Phillip von Stoch the German-born antiquarian and collector and the 2nd Duke relate how several of the pieces came to be in the collection.

Sard intaligo of a cow by Apollonides, Greco-Roman 1st century BCE

Carnelian intaglio depicting Priam, 1st century BCE/ACE

Aquamarine intaglio of a youth shouldering a bull, Anterotos c 50 BCE.

Stosch writes he is delighted to learn that the Duke has acquired the four famous carved gems of Apollonides, of Aetion, of Anterotos and of Dioscorides, and asks if the Duke could let him know on what sort of stones the originals are engraved so that he could note them in his book if he ever publishes an appendix.

The fragment of sard signed by Apollonides is engraved with a recumbent cow, the carver capturing with a few spare strokes the effort and motion of the beast rising to her feet and although damaged the fragment has been preserved, repaired as was traditional with gold.

Red sard cameo of Socrates, Agathemerus. Greek

Stosch writes he is delighted that Agathemerus’s Socrates has met with the Duke’s approval and explains that Monsieur Strozzi gave it to Stosch and for the same price that he is selling it to the Duke. Stosch says he would be very happy to have contributed to the Duke’s Cabinet. If, however, the Duke absolutely wishes to pay him, Stosch begs him to send in exchange a small dinner service in English pewter, which he really needs and which one doesn’t find in Rome.

Red jasper intaglio depicting Rufinae, possibly the martyred Roman Saint. Probably ancient.

In one letter Stosch notes his pleasure at seeing the 2nd Duke using a red jasper carved with an image of Rufinae to seal a letter to him, that gem, mounted as a ring is still in the collection.

Sardonyx cameo of Medusa, unsigned.

Their letters also describe a sardonyx Medusa when Stosch was honoured to receive the Duke’s letter via Monsieur Jagel, Court Clerk, with the enclosed bill of exchange of 100 scudi, which he paid to the owner of the Cameo of Medusa. He describes the cameo as not being "completely perfect, having the fault that all cameos of three colours have, it is most certainly antique and worth the price - for the stone, for the conservation and for the size, which Stosch has been assured of unanimously by experts”. Stosch continues to say that now he has learned of His Grace’s taste, he is well set up for helping in future.

A portrait, cabinet, letters, and gems in combination bring this world of collecting closer to us, it relates some of the excitement, pleasure, and pride in collecting these pieces. We also learn that, although highly valued and prized and stored in bespoke cabinets, they were also things for everyday use, used to seal letters and these associations are gathered into our understanding of them.

The gems were considered an essential component of any great collection alongside a library, drawings, paintings and sculpture. Lorenz Natter was engaged by the 4th Duke to catalogue the collection when they were kept in the plate room at Devonshire House, accessible to scholars and collectors who would sometimes receive impressions of them.

It was in this vein that the gems were preserved and appreciated until the time of the 6th Duke of Devonshire, when some of the Devonshire gems were used in the Devonshire Parure commissioned in 1856 by the 6th Duke of Devonshire for his niece Maria Granville to wear to the coronation of Tsar Alexander II of Russia.

The Devonshire parure image ©Thomas Loof

The appeal of these small-scale sculptures is enduring, in 2017 Laura, Lady Burlington, wore pieces of the Parure for Vogue magazine in celebration of the launch of Chatsworth's 'House Style' exhibition which she co-curated with Hamish Bowles & Patrick Kinmonth.

These gems continue to be worn and enjoyed by the Devonshires.