The Chatsworth House Trust charity has made a significant acquisition for the Archives in the form of a letter written at Chatsworth by Mary, Queen of Scots 446 years ago.

The letter will be on display at Chatsworth from 6 July until 13 October in the Collections Spotlight Gallery (included with all house tickets).

Mary, Queen of Scots at Chatsworth

In 1568, Mary escaped imprisonment in Scotland and fled to England, seeking the protection of Queen Elizabeth I. However, her strong claim to the English throne made her a threat to Elizabeth and she was taken into captivity.

George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury was appointed Mary’s jailer by Queen Elizabeth in 1569, and was honoured to accept what he believed would be a temporary responsibility. In fact Mary was to be in the custody of Shrewsbury and his wife, Bess of Hardwick, until 1584.

While most of her imprisonment was spent at Sheffield Castle and Sheffield Manor, she was also held at several of the Earl’s other properties, and visited Chatsworth on nine occasions. Although the Elizabethan house no longer stands, the Queen of Scots Apartments – on the east side of the house overlooking the Inner Court – still bear Mary’s name and are believed to be in the location of her lodgings.

The Archives at Chatsworth hold many significant documents from Bess of Hardwick’s time, and people naturally assume that there are documents of Mary’s amongst these. However, until last year, the Archives contained no documents written by Mary at all.

Requests for assistance

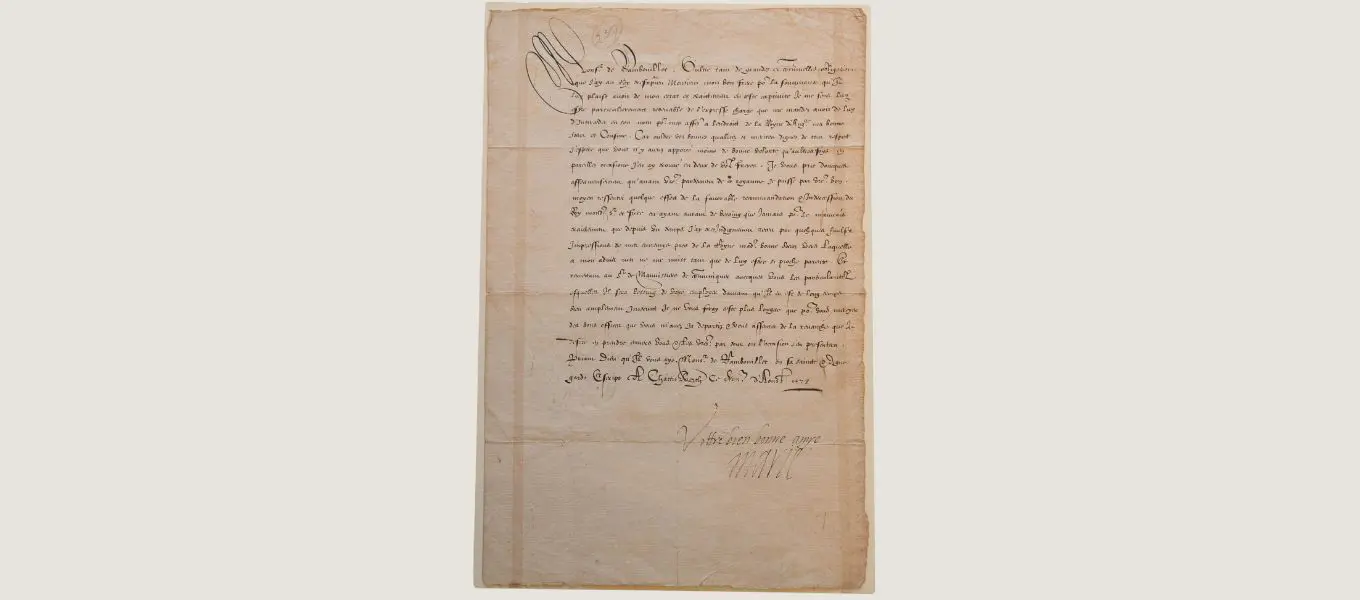

Mary spent her formative years in France, and, as Dowager Queen of France, she looked to the French for help in her captivity. The newly acquired letter was written at Chatsworth on 31 August 1578. Its recipient was French ambassador Nicolas d’Angennes, sieur de Rambouillet, who had been sent to England by the French King, Henri III, on a mission to intercede with Queen Elizabeth on Mary’s behalf.

In the letter, Mary expresses her appreciation to her brother-in-law the French King, Henri III, for his support. She reflects on her position as a prisoner and complains about the lies that have been spread by her enemies, although she is careful not to blame Elizabeth directly for the poor treatment she has received.

She acknowledges her closeness to Elizabeth and therefore also to the throne of England – which was the very reason why Elizabeth would ultimately never be prepared to release her.

Mary preferred to correspond in the French language, and her Chatsworth letter is written in French. She employed secretaries to write much of her correspondence. The body of this letter is written by a secretary, but it includes Mary’s distinctive sign-off and signature at the foot.

Mary wrote thousands of letters during her captivity. They were her only means of communication with the outside world. They helped to maintain her networks of support, and were central to various plots and intrigues. Correspondence was often smuggled in and out, sometimes written in code, to try and avoid interception.

Royal treatment

This required constant vigilance on the part of her custodian. The Earl of Shrewsbury was also required to treat Mary as a Queen. Although a prisoner, she was allowed to maintain her own separate household which averaged 40-50 people. She had two meals a day, each of which included 16 different dishes for her to choose from.

Supporting this extended royal household was expensive, and the allowance Shrewsbury received from Queen Elizabeth never covered costs. As the years passed, the responsibility of maintaining Mary put strain on the marriage of the Earl and his wife Bess, and it played a factor in their ultimate separation in 1583.

We are delighted to see Mary’s letter return to Chatsworth for the first time since it was written, where it will take its place in the Archives alongside letters of other key players in Mary’s drama: Elizabeth I, the Earl of Shrewsbury, and – of course – Bess of Hardwick.

Read Mary's letter

Monsieur de Rambouillet (i), besides the large and continuing debt which I owe to the most Christian King, monsieur my good brother (ii), for the regard it pleases him to pay to my situation and treatment during this imprisonment, I feel particularly beholden to him for the express command which you inform me you have from him to intercede in his name on my behalf directly with the Queen of England, my good sister and cousin.

For, besides your good qualities and merits, which are worthy of all respect, I hope that you will bear no less good will than [that which] before, on similar occasions, I found in two of your brothers.

I therefore entreat you affectionately that, before your departure from this kingdom, I might, through your good means, feel the effects of the favourable recommendation and intercession of the King, my aforesaid lord and brother, having [as I do] as much need of it as ever, because of the ill treatment which for some time I have unworthily received [on account of] the false impressions [made] by my enemies [on] the Queen, my aforesaid good sister, with whom, in my opinion, nothing does me greater harm than being so closely related.

Leaving to the Sieur de Mauvissière to communicate with you the particular areas in which it will be needful to employ you (iii), all the more so since he has been concerned with them for such a long time, I will not make this [letter] longer for you except to thank you for the good offices you have already completed for me, and to assure you of the repayment I desire to make to you and yours whenever the occasion presents itself.

Praying God that he keeps you, monsieur de Rambouillet, in his holy and worthy protection.

Written at Chatsworth, this last [day] of August, 1578.

Your very good friend,

Marie

With thanks to Dr Emily Wingfield, Senior Lecturer in English Literature at University of Birmingham for the English translation of Mary's letter.

Hear Mary's Letter Read Aloud

You can also listen to a recording of the letter being read aloud by Louise Calf.

i. French ambassador: Nicolas d'Angennes, sieur de Rambouillet (c. 1531 –c. 1611)

ii. Henri III (1551-89), younger brother of Mary’s first husband, François II.

iii. Michel de Castelnau, Sieur de la Mauvissière (c. 1520–1592), ambassador to Elizabeth I.

A painting by Charles Robert Leslie believed to depict Mary Queen of Scots writing a letter, early 19th century.