Sir Joseph Paxton (3 August 1803 – 8 June 1865) was a visionary, described in his obituary in The Times, in June 1865, as ‘the greatest gardener of his time, the founder of a new style of architecture, and a man of genius’.

Born into a humble farming family in Bedfordshire, Paxton was the archetypal self-made Victorian, whose inquisitive nature and industrious energy propelled him to the forefront of a portfolio of fields – architecture, engineering, horticulture, and landscape design.

The Chatsworth Garden and Estate are intrinsic to Paxton’s story; when he arrived in 1826 he was only 23 years old and the garden needed much work.

Paxton had been working in the Horticultural Society's experimental gardens at Chiswick, first as a student gardener and then as a foreman in charge of the arboretum. The 6th Duke of Devonshire enjoyed walking in the gardens and talking to Paxton. The Duke convinced him to become his Head Gardener at Chatsworth.

Paxton inspired in the Duke an intense interest in horticulture. Together they changed the garden radically, introducing exotic species and giant rockeries which were the result of garden tours in England and Paris and a grand tour of Europe, where they visited Switzerland, Italy, and Turkey.

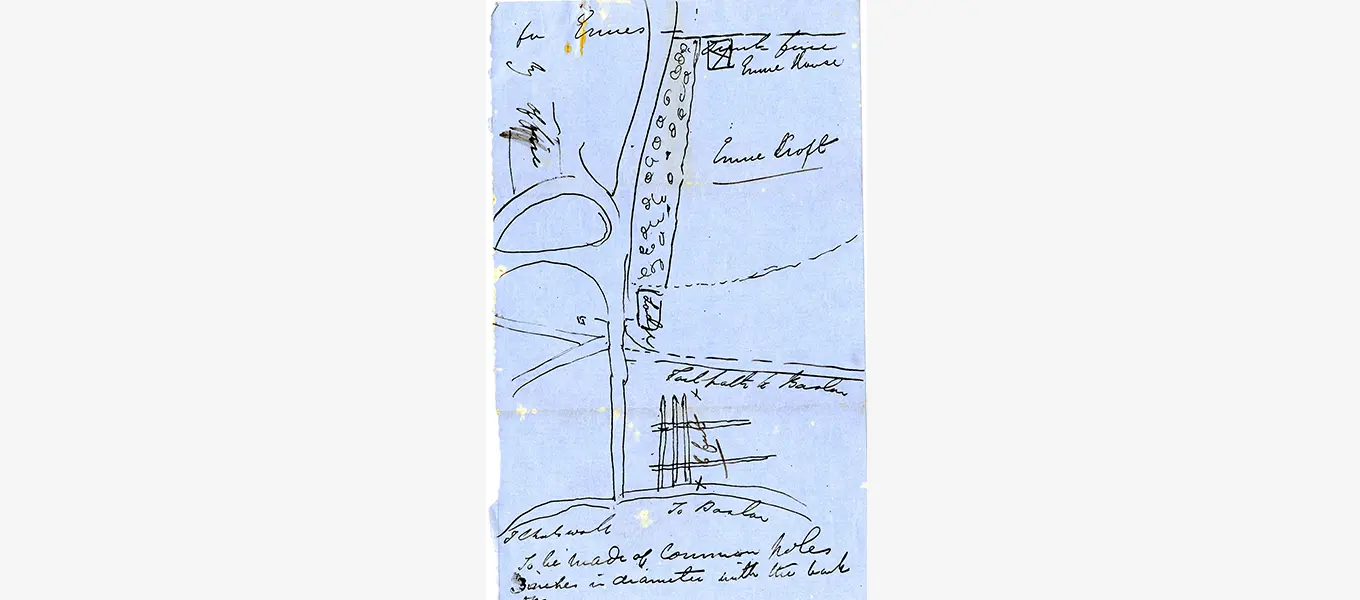

Paxton designed and constructed the Emperor Fountain (1844) in the Canal Pond and also the Great Conservatory (1836-41), the forerunner of the Crystal Palace built for the 1851 Great Exhibition. The Great Conservatory became derelict during the First World War as it became too costly to run, and it was demolished soon after. The maze now grows in its place.

By the time he retired as Head Gardener in 1858, Paxton had left an indelible mark upon the landscape and Chatsworth’s garden was known throughout the world. Read the full extent of his impact at Chatsworth in the history of the garden.

For Paxton, Chatsworth was his training ground, the Great Conservatory was the progenitor of arguably his greatest achievement in any field – the Crystal Palace; designed and built for the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Crystal Palace was roughly 25 times the size of the original; whilst the innovative use of uniform parts and mass production created an economy of scale that brought Paxton’s design in at 28% of the cost of his nearest rival for the commission.

Of Paxton’s horticultural successes, one outshines all others; the cultivation of the Musa Cavendishii, or the ‘Cavendish Banana’.

Bought for £10, the plant was cultivated by Paxton in ‘plenty of water, rich loam soil and well-rotten dung’. It flowered at Chatsworth for the first time in November 1835. By May 1836 over one hundred fruits were ripening. Later re-exported via missionaries to Samoa, this plant is today the ancestor of the most commercially grown bananas worldwide. Seven billion Cavendish Bananas are eaten in the UK each year alone.

Unsung Hero

It was during Paxton’s many enterprises away from Chatsworth that his wife, Sarah, came into her own. Sarah Paxton (nee Brown, 1800 - 1871) was the daughter of a small engineer and Matlock mill owner. Her aunt, Sarah Gregory, was housekeeper at Chatsworth. They married in 1827 not long after Joseph arrived.

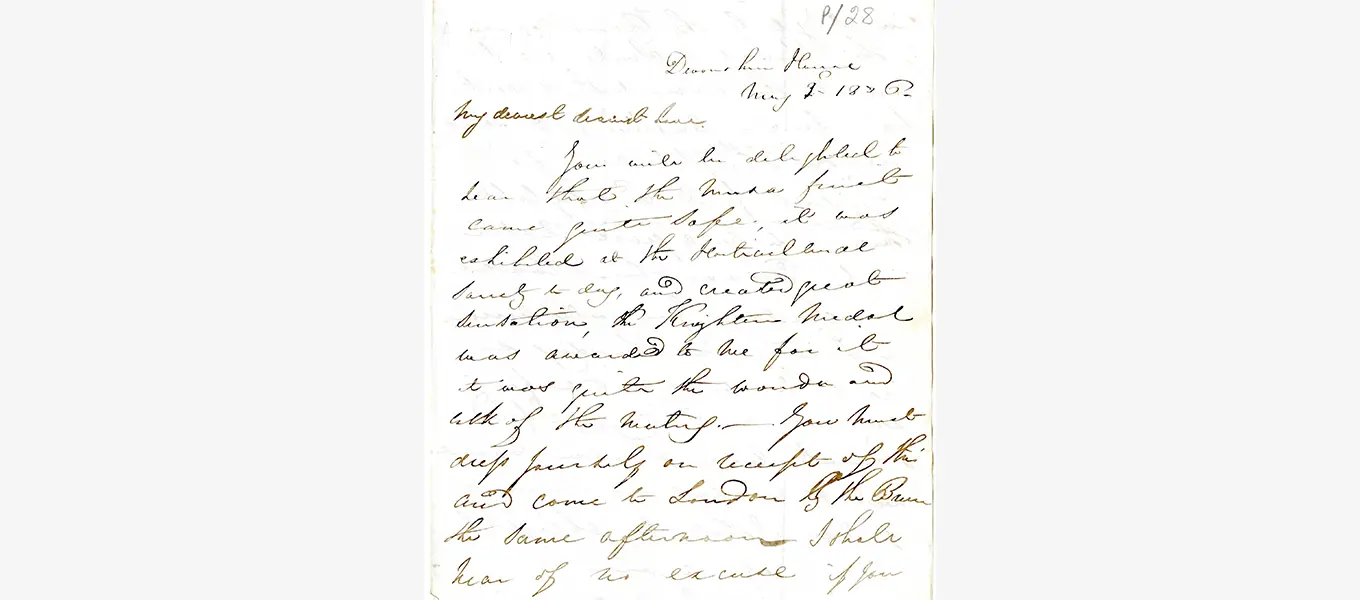

Sarah Paxton is considered one of the unsung heroes of the nineteenth-century; she took over many of the duties of Head Gardener and Land Agent in Joseph's absence; acting as his proxy in the garden, enacting his instructions sent by letter. This put a huge level of responsibility on her, expecting her to manage the foremen, and instruct the men directly; she had an in-depth knowledge of plants in the garden, as well as impressive business and financial management skills.

Much of Paxton’s Chatsworth was constructed under the trained eye of Sarah rather than Joseph and it is without doubt that Joseph would not have achieved the feats he did without Sarah’s intelligence and hard work in a Victorian world dominated by men.

Horticultural History Makers

Thanks to a generous grant from AIM Biffa Award, Chatsworth was able to explore how these two Victorian pioneers impacted the world we know today.

Archival research into ‘The Paxton Papers’ - of which there are circa 2,000 letters both from and to the pair within Chatsworth’s archives - tell their fascinating stories and reveal their ground-breaking enterprises in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). These stories have informed new interpretation on display in the Chatsworth Garden.

There are also a number of educational resources available designed to introduce children of all ages to Joseph Paxton and his work at Chatsworth.

Header image - cross-written letter from Sarah to Joseph, reporting on progress building Chatsworth's Great Conservatory