'Worth, Inventing Haute Couture' is showcased at the Petit Palais in Paris until 7 September 2025. This is the first large-scale exhibition dedicated to the legendary Worth fashion house and its role as the originator of haute couture.

The exhibition features over 400 objects displayed in chronological order, ranging from clothing and accessories to paintings, graphics, objets d'art, and archive materials.

The broad-ranging exhibition includes pieces from the Palais Galliera collections as well as rare and prestigious items on loan from leading international museums, such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Palazzo Pitti, and many private collections.

At the request of the exhibition curators, Annick Lemoine of the Petit Palais and Miren Arzalluz of the Palais Galliera, the Chatsworth House Trust charity has lent the exhibition the striking "Zenobia Queen of Palmyra" ball gown, created for Louise, Duchess of Devonshire (1832-1911) to wear to the 1897 Devonshire House Ball, in honour of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee.

The loan is further evidence of the charity's commitment to share the art and artefacts preserved in the Devonshire Collections with as many people as possible.

About Worth

British-born Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895) left a job trimming bonnets in Bourne to move to London to work in the textile trade. At the age of 21 he took a role at Maison Gagelin, a textile merchant in Paris, as a salesperson and dressmaker. He quickly made a name for himself and worked his way up to partner.

In 1858, he opened his own salon on the first floor at 7 Rue de la Paix with business partner Otto Bobergh, called Worth & Bobergh.

Worth is referred to by historians as the 'father of haute couture'. Until he reshaped the relationship, an aristocratic client would visit a designer with their own fabric and ideas, and dictate what was made. Instead, Worth produced looks that a customer could purchase, and was the first person to use live models and runways to display his creations. He was responsible for the shift in power from client to creator.

Around 1860, Worth enlisted what we'd define today as an 'influencer'; he convinced a female courtier inside the royal court of Napoleon III to wear his dresses in the hope of getting them noticed by society. As a result, he secured the patronage of Empress Eugenie, the Princess von Metternich, and the imperial court, and quickly became the most sought-after designer in Paris. His designs have been immortalised in portraits of prominent women, painted by the era's greatest artists, proving how adored his clothing was.

Worth was the first to sew labels in his garments, signing his creation as an artist might sign a canvas, and photographed each of his looks, assigning it by name or number. He led the establishment of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture (now known as the Federation de la Haute Couture et de la Mode, France's governing fashion body) in a bid to prevent overseas markets from copying his designs.

Following the departure of Bobergh in 1870, the house of 'Worth' continued to rise to fame, at one point, it employed over 1,200 people.

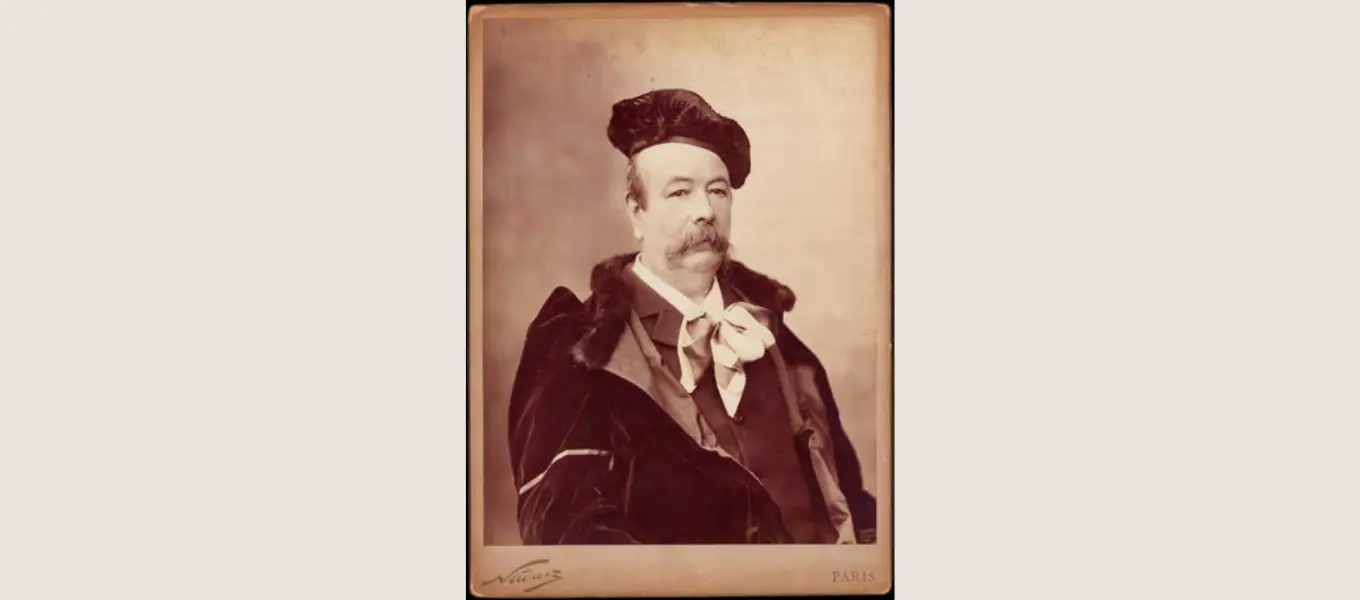

Above: Charles Frederick Worth 1892 By Nadar. Credit Librairie Diktats Courtesy Petit Palais

"A large series of portraits (photographs and prints) reflects Charles Frederick Worth's preoccupation with his image. In their great diversity, they consistently depict the couturier as an artist. Posing like a Rembrandt of fashion, wearing a beret or a toque and enveloped in ample and timeless drapery, the man seems to express his conviction that haute couture is a form of art." Petit Palais.

On his death in 1895, he was succeeded by his sons Jean-Philippe and Gaston Worth. They were successful in keeping their father's legacy alive while adjusting styles to match the silhouettes of the time.

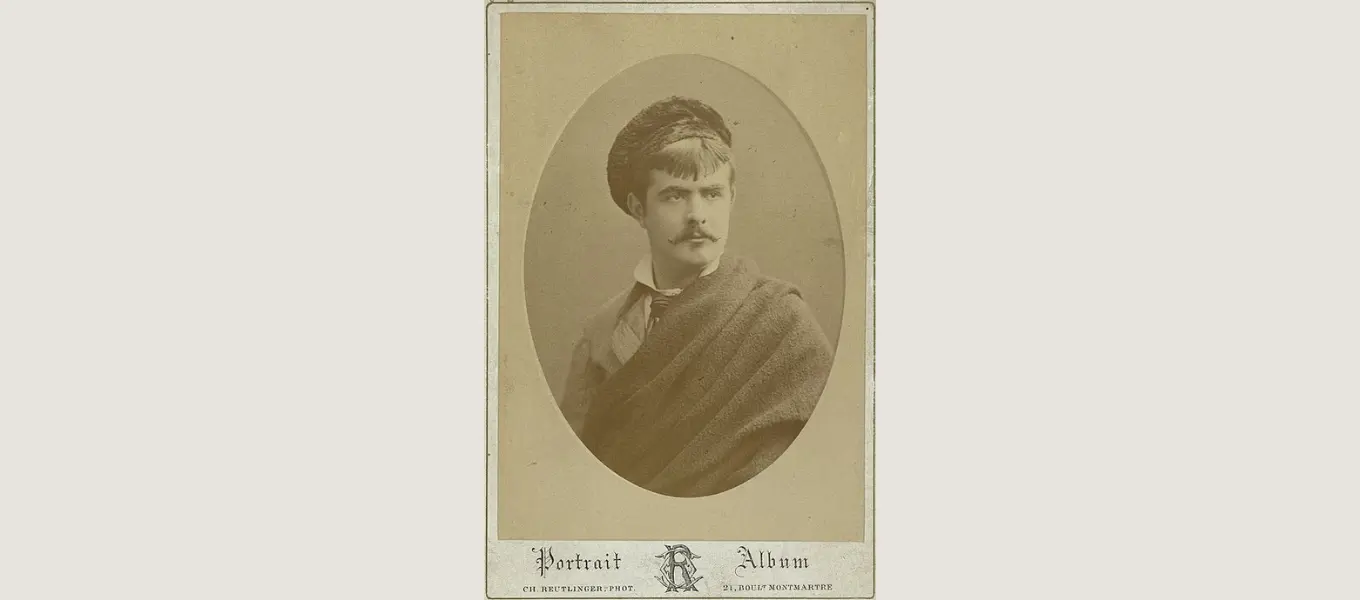

Jean-Philippe was the creative director when Duchess Louise was a client of the House of Worth. In the photograph below (Rijksmuseum, public domain), we see him posing similarly to his father, as an artist and perhaps even wearing the same beret.

Duchess Louise was known for her grand parties at Devonshire House in London. Attended by royalty as well as the aristocracy, they were an important get-together in the annual social calendar, on a par with today's Met Gala or awards ceremony. Guests would go to the finest and most sought-after fashion houses for their outfits.

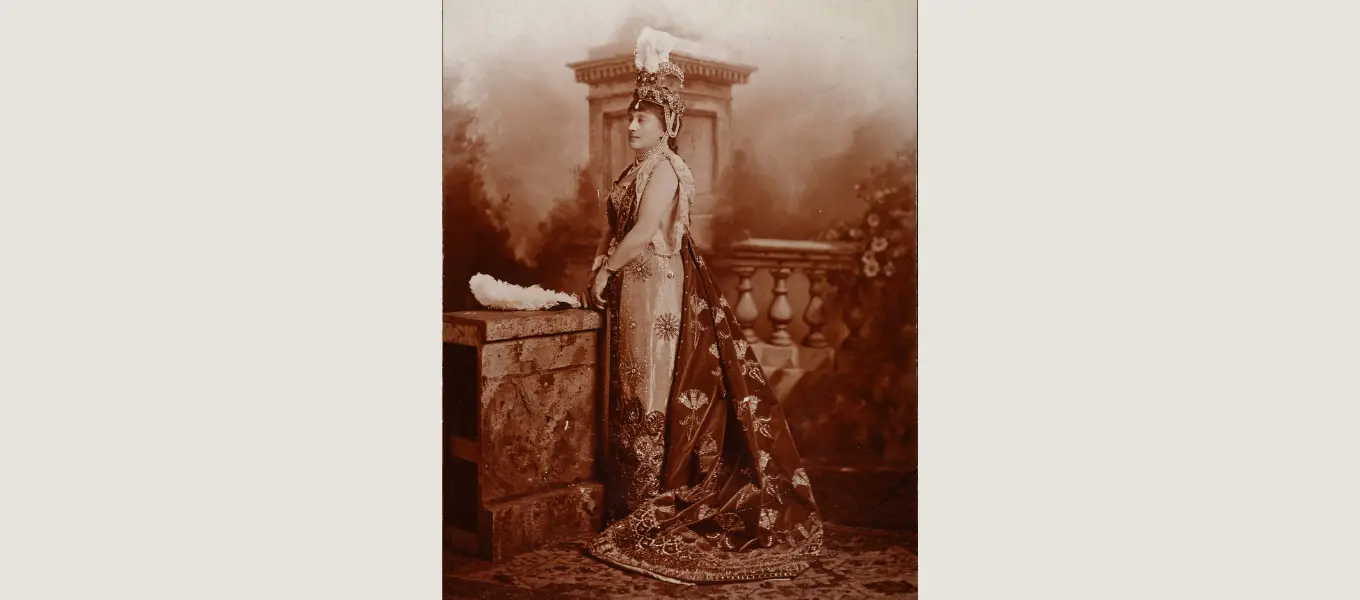

For the grand 1897 ball, Duchess Louise opted to portray Zenobia, the third-century Queen of Palmyra, an idea which may have been inspired by Inigo Jones’s costume designs for court masques preserved by Chatsworth House Trust in the Devonshire Collections.

Image: Duchess Louise wearing the Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra ball gown and headdress, credit Lafayette

The Queen of Palmyra gown comprises a skirt of gold gauze, appliqued with tinsel medallions and peacock plumes worked in bright foils, wire coils and spangled with sequins, which is worn over an ivory satin underskirt wrought over with silver thread and diamonds.

Attached to the shoulders is a long graduated train in vivid emerald green velvet, appliqued with velvet and gold work in an eastern design and studded with jewels.

Preparing the delicate dress

The dress was designed for a single night of wear and, as such, was crafted using delicate fabrics and threads upon which were fixed multiple jewels, some of considerable size and weight.

Professional conservation completed around a decade ago has ensured that the fabrics and fabulous colours can be admired for many years to come, however, the original metal clasps holding the jewels in place have started to fail and further conservation is required.

As a result, the dress’s outing at Petit Palais will be its last until funds can be raised for investigation and repair by Chatsworth House Trust, the registered charity dedicated to the preservation of the house, collections, garden, woodland and parkland.

Preparing the dress for transportation and display has to be undertaken with considerable care, with each element mounted onto a mannequin that is then built up with padding to absorb some of the weight and reduce the stress placed on the delicate fabrics and fastenings.

Learn more about the gown in this short film

We use platforms such as YouTube and Vimeo to display videos. These require the use of cookies, for which we need your consent. To watch this video, please click here to allow cookies.

Chatsworth House Trust (registered charity 511149) is dedicated to looking after the house, collections, garden, parkland and woodlands for the benefit of everyone.

All income from ticket sales, Gift Aid, our Chatsworth Friends and Patrons programmes, partners, sponsors and funders goes directly to the charity and is reinvested in the upkeep, preservation and improvement of Chatsworth, our learning programme, and essential conservation work, such as the restoration of the Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra ball gown.

Find out more about the charity and how you can support its work here.

The End of An Era

In the 1920's, Gaston’s sons, Jean-Charles and Jacques, took over the House of Worth, successfully matching the opulence and character the Worth brand had become renowned for. The house eventually closed in 1956.

The 'Worth, Inventing Haute Couture' exhibition celebrates the fashion house's ability to create stunning pieces for all times of day and all occasions, and features examples of daywear, opera coats, tea gowns and ballgowns, including Duchess Louise's.

Learn more about the exhibition here.

Chatsworth House Trust

Chatsworth House Trust is the registered charity dedicated to preserving the house, collections, garden, woodland and parkland for everyone. Find out more about its work.

Louise, Duchess of Devonshire

Duchess Louise was a society beauty, Mistress of the Robes to Queen Victoria, and hostess of the exclusive Devonshire House ball.

Devonshire Collections

Discover the art, textiles, sculpture, jewellery and more preserved by the Chatsworth House Trust in the Devonshire Collections.

Dress image credits: Thomas Loof and Chatsworth House Trust