Prefer to listen? Play the film to hear author Louise Calf read this blog aloud.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, deciding their treasures would be safer amongst a group of girls than a battalion of soldiers, Chatsworth House became home to a school. But what must life have been like for a school girl living in Chatsworth House? And, since this is my area of research, what was it like having a working theatre to play in? Thankfully, just before lockdown, I decided to do a bit of digging.

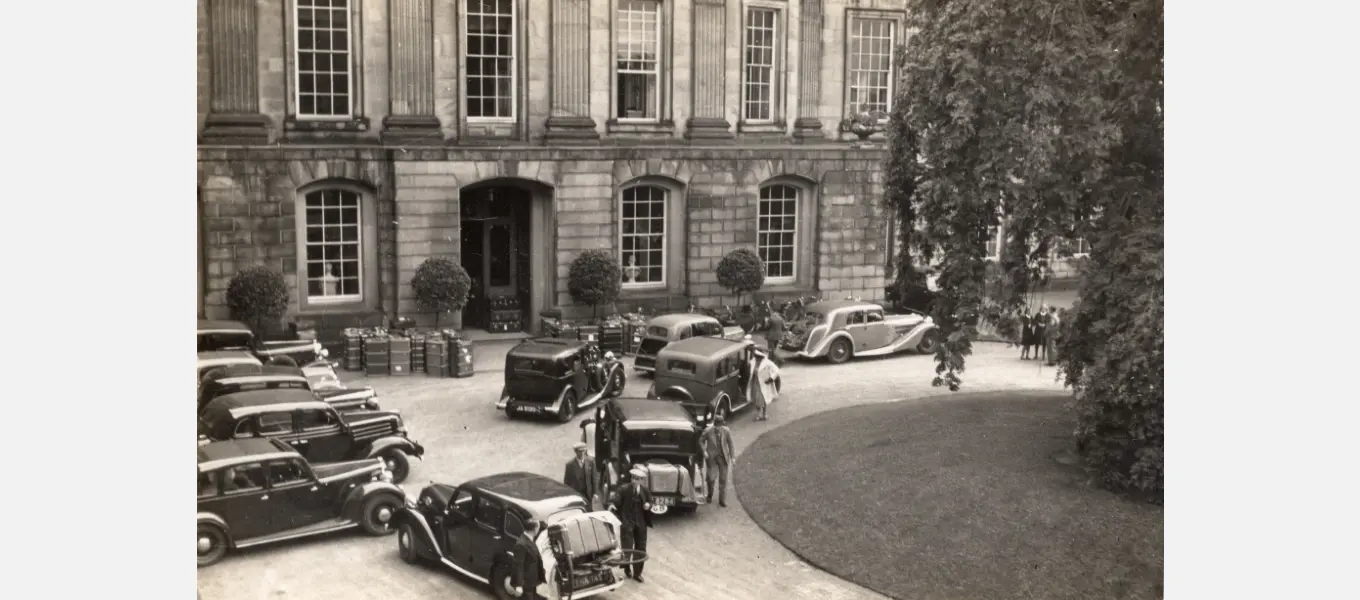

So, what do we think we know about all this? Well, in September 1939, a week or so after war had been declared, 250 school girls, 36 teachers and 26 pianos arrived on the doorstep of Chatsworth House.

Their school in North Wales, Penrhos College, had been taken over by the Ministry for Food, so the Headmistress, Miss Smith, and one of the school’s Governors, Professor Yorke, worked out a deal with Chatsworth and they all came here.

It was important for Miss Smith that the girls’ experience and education remain as seamless and consistent as it had been in Colwyn Bay. She and some other staff members worked with Chatsworth to find spaces that could accommodate all the standard lessons: Art was taught in one half of the Orangery, Biology and Physics in the Kitchens, Chemistry in the Stables (the Bunsen burners being a bit risky in a house full of treasures). The Squash Court became a gym, the Laundry Room used for teaching domestic science, while most of the State Rooms became dormitories: rows and rows of single beds and the occasional wardrobe.

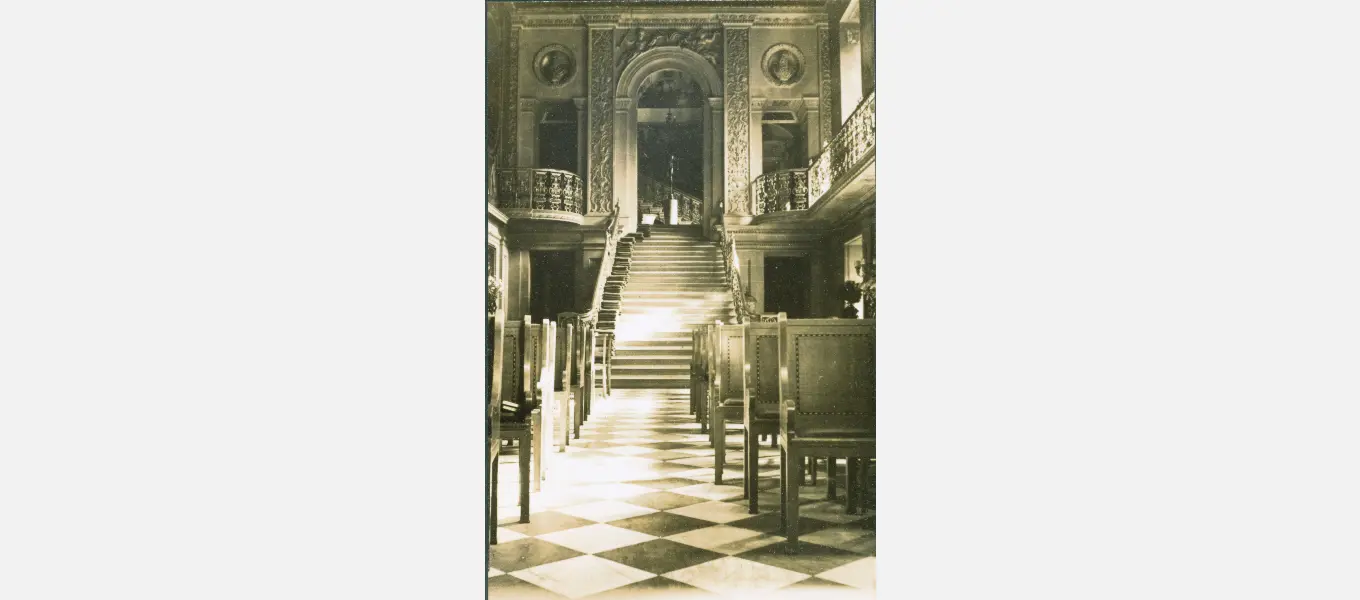

The Painted Hall was the heart of the operation, hosting assemblies – where news of the progress of the war was relayed to the girls – morning and evening chapel, as well as film nights on Saturdays. In her memoir, ‘School Days at Chatsworth’, Nancie Park recalls the ceiling being a source of endless wonder, ‘especially if concentration waned during the sermon.’ For an idea of what school life must be like in such exquisite surroundings, I can’t recommend Park’s book enough (you can buy it in the gift shop).

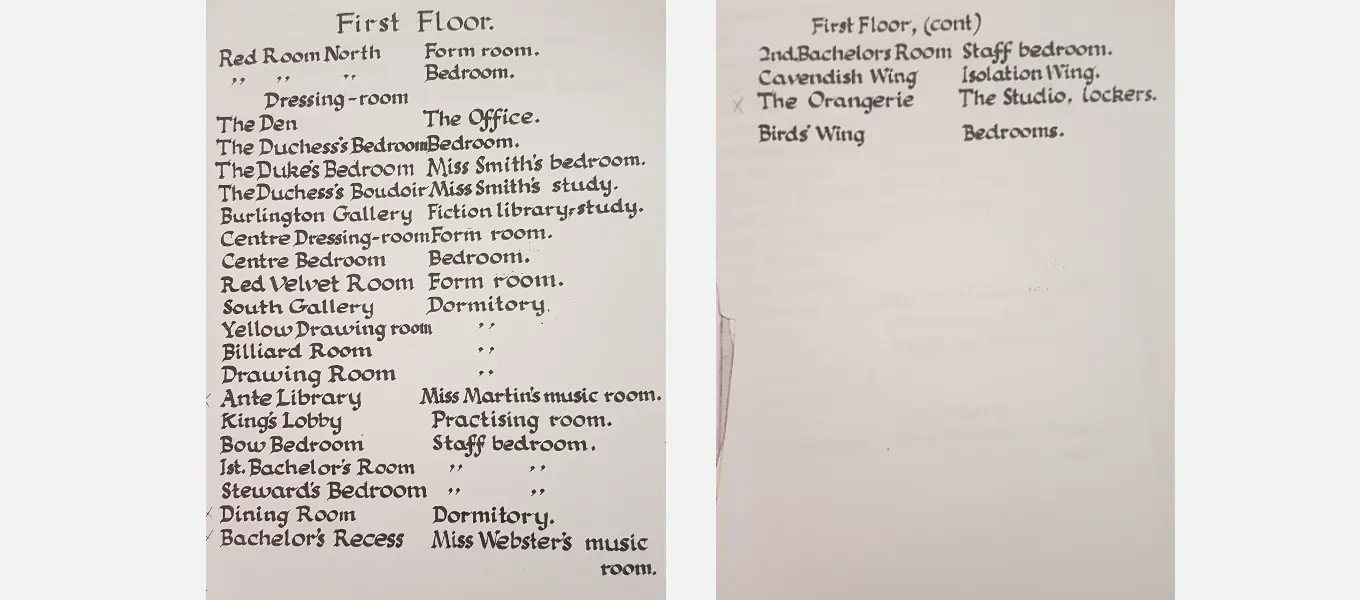

Most of how we understand Penrhos College’s use of Chatsworth during the war comes from this memoir – along with at least two others – a painting by Edward Halliday showing the State Drawing Room as a dormitory, and a list.

This list details all the rooms used by the school, and how the use was converted. It’s the go-to, quick-to-check document if you’re wondering how some of the rooms we see today were experienced by school girls 80 years ago. Alongside the more descriptive material, this list acts as a sort of cursory overview of the house during war time. My problem is that the Theatre does not appear on the list. Well, you might think, perhaps the Theatre wasn’t really used at this time – the estate is expansive and there’d be more than enough space to house all the necessary school activities. Or, you might think, maybe they only used it occasionally, when they needed somewhere with lots of space and no interruptions (which, incidentally, is how it’s used a lot today), but not enough to warrant inclusion on The List. And you might be right… but I decided to check.

Remember those 26 pianos? Every source tells us just how highly music was placed on the curriculum and recitals from visiting musicians were usually held in the Theatre. Among ‘a host of instrumentalists, trios and duos,’ one performance was particularly memorable for one alumna…for all the wrong reasons:

"One Saturday afternoon the renowned pianist, Cyril Smith, came to perform for us. I was asked to conduct him from the House to the theatre. On arrival there, he bowed, flicked up his tails and sat at the Grand Piano. He had no sooner started to play a lovely concerto than all the central heating radiators started clanging horribly. To my dismay, he stopped playing and bowed to me and I realised I had to do something about the emergency. I went round all the radiators and screwed down each knob. To my relief, peace reigned once more and the concert was enjoyed by all of us.

"Imagine my horror when a few hours later I was summoned by the Domestic Science Mistress to be told that I had caused the central heating system to flood (2' deep) the Domestic Science rooms below the theatre - carrots, cabbages and cake ingredients along with pans and kettles were floating in disarray."

Not all musical occasions went so disastrously. Swiss singer and composer, Gustave Ferrari, elicited an enthusiastic report from Maureen Sewell in February 1940 by coaching ‘various members of the School to mime his songs, causing much amusement among the performers.’ One of the songs, translated from the French as ‘The Cycle of Wine’, had members of the Lower Vth form miming, ‘the history of a grape from the time it is grown to when it is drunk’. While we can only imagine the form this might have taken and the ensuing hilarity on stage, it chillingly reminds me of drama school and the horror of being asked to represent a crumpling crisp packet.

Music was at the centre of much of the cultural life at Penrhos but the Theatre also played host to the ubiquitous school play, only performed by those girls who took lessons in elocution (which were also held in the Theatre).

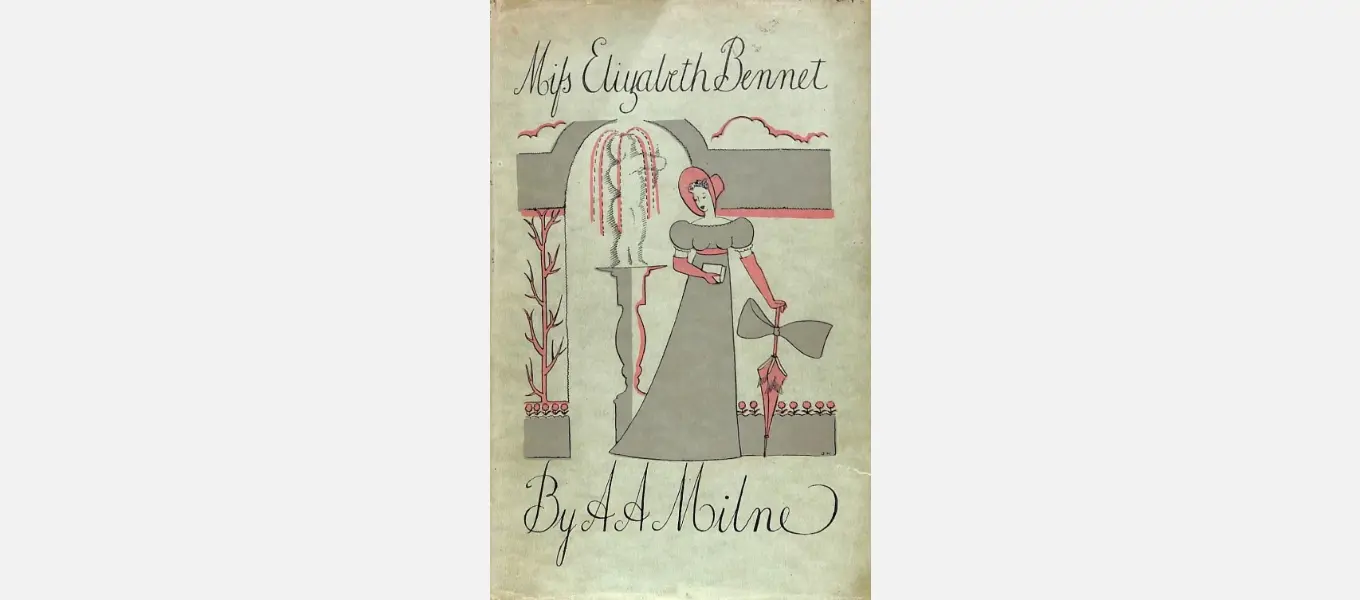

The school magazine records this as taking place late in the Winter term and, in 1939, the play was ‘Miss Elizabeth Bennet’ by A. A. Milne. So, that’s the author of ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’ writing an adaptation of ‘Pride & Prejudice’, which was then staged in Chatsworth House – a building now so closely aligned to the Austen novel that international students of English literature come all the way to the UK just to see it.

Neither were the similarities between Chatsworth and the fictional home of Mr Darcy lost on Penrhos’ sixth former Brenda Morris who reported that, ‘It was a mere coincidence that, during the play, mention was made of Pemberley Manor - "the most beautiful estate in Derbyshire which is to say the most beautiful in England," - which, strangely enough, appears to be a reference to Chatsworth!'.

In one unknown year, the prefects staged a production of ‘The Admirable Crichton’ by J. M. Barrie, another well-known children’s author. The accommodating Chatsworth gardeners lent the girls potted shrubs to evoke the atmosphere of a jungle. Unfortunately, this standard of professionalism was somewhat undermined by a costume mishap as Lord Loam, ‘duly cushioned to appear the right shape’, lost her cushions at a critical moment mid-performance. It is unsurprising and a bit of an understatement, then, that so many girls describe the productions in Chatsworth’s theatre as ‘memorable’.

The girls at Penrhos were organised into Houses, and each House had the responsibility of entertaining the rest of the girls once a year – an occasion known, fairly unimaginatively, as House Entertainments.

While at Chatsworth, these featured the playing of a film in the Painted Hall, followed by dinner and then dancing in the Theatre. Nancie Park describes a typical war-time, makeshift band at these events, with one girl ‘humming behind a comb, on to which toilet paper had been stretched.’

Naturally, each House strove to make its mark on the occasion. In the winter of 1939, Shackleton House’s band embraced the festive season, ‘arrayed as crackers, in red crepe paper, rather insecurely held together by pins.’ While in the Spring of 1940, some of the more enthusiastic members of Scott House spent the afternoon of their Entertainments blowing up balloons with which they dressed the Theatre, hanging them from the balcony and lights. Hitting a more dramatic note, they dressed their band entirely in black, punctuated only by ‘musical symbols in silver attached to their costumes’.

During a period when the entire country was wrangling with exceptional circumstances, when letters from home might report difficulties or – in the worst cases – family loss, when their new home at Chatsworth was impressive but freezing cold, Miss Smith recognised how important laughter, creativity and camaraderie were for the girls in her care.

The list I mentioned earlier is recorded in the archival catalogue as being created in 1939, the year Penrhos arrived at Chatsworth. While this needs to be confirmed, it seems likely that it was created as a guide for new arrivals to the house, pinned to a wall somewhere, to help girls and teachers alike work out what was what and what was where.

By being left off the definitive list, by failing to be prescribed as anything in particular, the Theatre was free to be anything the girls wanted it to be. Its purpose could be invented and reinvented as circumstance dictated: today a concert hall, tomorrow a jungle. And, through playing in the House band, embodying the life cycle of a grape, or by being whisked away to Pemberley on the clouds of imagination, the power to dictate the role of the Theatre lay not with Miss Smith, or any of the teachers or staff, but with the girls themselves. And isn’t this precisely what theatres are? Anything and everything you can imagine.

For more information on Penrhos’ occupation of Chatsworth, Sotheby’s have a neat summary here, while Chatsworth produced these learning materials for their 2014 exhibition ‘Chatsworth in Wartime’.

Listen to a 1967 BBC Radio 4 adaptation of Milne’s ‘Miss Elizabeth Bennet’ here.

The Devonshire Collections Archive catalogue number for Penrhos College is CH4.